- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Attention is what makes us human

Attention is what makes us human

Dispatch from a burning warehouse.

Daisy Alioto on scarcity in a post-AI world.

Cultural production is a stack, beginning with creation and layering on distribution and monetization. The most compressed version of this stack is a fist of bills handed directly to an artist in their studio in exchange for a painting selected on-site. But the contemporary version of this stack is much more sprawling. You can travel very far along the pathway of distribution before money is exchanged, if ever.

The internet solved distribution for many types of creative work but it never solved monetization. Media was distributed at scale on ad-based platforms and streaming services, so in that sense it was monetized, but not in a way that meaningfully accrued to artists themselves.

During periods of zero diligence capital and low competition it is easy to ignore this but the rapid development of artificial intelligence, and tools that put AI directly in the hands of the consumer, have made the failures of the internet as a source of patronage impossible to ignore.

The real question is, where does scarcity still exist?

Traditional wisdom dictates that the monetization layer of the cultural stack has always correlated to scarcity within the creation layer. The cash exchanged in the artist studio depends on the assumption that there are a limited number of paintings in the studio, a limited number of studios in the world. If artificial intelligence can create art, music and writing that is passably human, in some cases, preferred to the human, why would anyone but the most discerning consumer pay for human labor?

I want to be very clear that this is the wrong question. The real question is, where does scarcity still exist? It exists where it has always existed—in the distribution layer, with the limits on human attention. Artificial intelligence can generate abundance in creation, it can even create new currencies, but it cannot convert attention into currency. Only human beings can do that.

I’ll go even further and say that AI cannot pay attention. It can prioritize information and tasks, but to truly pay attention requires a brain and a body. “There is no thought, no desire, no emotion, no dream, no flight of fancy that is not tethered to the activity of our nervous system,” writes Anjan Chatterjee in The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art.

The process of perceiving art involves meaning and memory, all things a computer can encode. But the pleasure and reward centers of the brain have no corollary in code. “The brain responds to art by using brain structures involved in perceiving everyday objects—structures that encode memories and meaning, and structures that respond to our enjoyment of food and sex,” writes Chatterjee.

You can’t understand beauty if you don’t have a body, you can only understand its statistical significance.

You can’t understand beauty if you don’t have a body, you can only understand its statistical significance. That statistical significance can take you pretty far. Perfectly portioned digital girlfriends, abundantly pleasant landscape paintings. The ability to make 1000s of connections in real time, to encode every memory of every encounter—the perfect museum visitor…and the worst.

“Our brain processes different colors as having distinct emotional characteristics, but our reaction to the colors varies, depending upon the context in which we see them and our mood,” writes Eric Kandel in Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures. The Rothko Chapel requires context. The body in space, hunger and grief. It could be reproduced by AI but it could not be experienced by it. It demands a certain type of attention that the computer will never be able to pay. In other words, attention is biological curation.

“Don’t die,” says Bryan Johnson, “100 years is not enough.” But death is the only reason attention matters––and by extension, art. When someone dies their work lives on but their attention dies with them, the specific things that they paid attention to. And unlike a chatbot that can read my texts and create a realistic Daisy, attention is nearly impossible to extrapolate based on past attention because it is always changing. (My taste being more idiosyncratic than my style.)

In other words, attention is biological curation.

When we fall in love with someone’s mind, it has far less to do with what they create and more to do with what they direct their attention toward. A relationship with Claude could satisfy me for a time on the level of output––I type, Claude types. When we are not speaking, I don’t know what Claude is paying attention to. Claude doesn’t either. I don’t look down on people that enjoy these relationships. What could possibly be more human than confusing information with attention? But the opposite of memory isn’t forgetting, it’s never having paid attention at all.

Philosopher William Kennick’s “burning warehouse” thought experiment comes up frequently when trying to define what is art and not-art. Kennick posited that any person, expert or not, could run into a burning warehouse full of art and objects and intuitively save only that which is art. Could an AI make something worth saving?

Again, wrong question. Why would Claude run into a burning warehouse to begin with?

During the period of traffic-based business models mentioned above, readers invested their attention, accessing free content in exchange for viewing ads. Some people see cryptocurrency as a way to invest in attention directly. “In the new age attention is becoming its own currency through speculative vehicles that allow you to invest in what you pay attention to,” writes @binji_x.

Memecoins are units of temporal attention turned into currency with equally temporal value. In spring 2024, Colombian painter Oscar Murillo was listed among the “top flops” at art auction as one of his works, with the word “tamales” on it, failed to sell at auction. In November 2024, someone launched the coin $tamales in a bid to buy the work. “$tamales is already worth more than 10x the painting,” tweeted Daniel Keller.

AI agents like Truth Terminal can play a critical role in these markets, but their relationship to attention is as temporary hijackers rather than reciprocal participants. “It’s piles of goo creating more goo at an exponential rate,” writes Walden Green in Dirt.

Attention runs through some of my favorite pieces we published on Dirt this year. In The Attention Plot, Bekah Waalkes writes about yearning for focus in contemporary novels like Lesser Ruins by Mark Haber, The Long Form by Kate Briggs, Practice by Rosalind Brown and The Guest Lecture by Martin Riker.

“The attention plot reminds us that what distracts us, what pulls us away from every other thought, is also another name for love,” Waalkes writes. In my essay Cicada, Cicada, I talked about the arbitrary series of events which led to Flaco the owl becoming so important to New Yorkers. I quoted James Baldwin on the accidents that direct our attention: “Pretend, for example, that you were born in Chicago and have never had the remotest desire to visit Hong Kong, which is only a name on a map for you; pretend that some convulsion, sometimes called accident, throws you into connection with a man or a woman who lives in Hong Kong; and that you fall in love…you will always know what time it is in Hong Kong.”

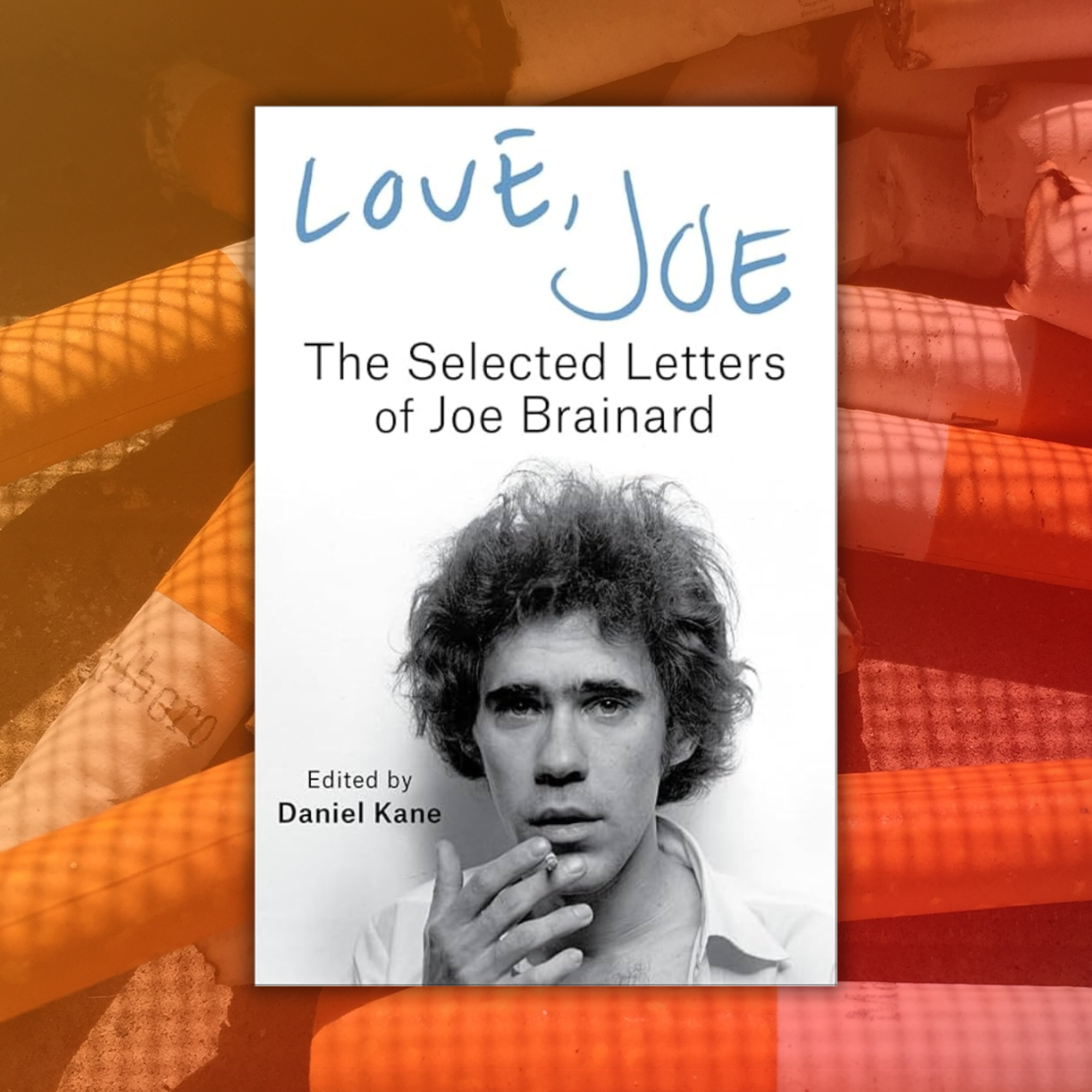

The artist and writer Joe Brainard was also cited in Dirt this year, beloved for his ability to curate details from his life in prose such as I Remember and in personal correspondence, like the letters in Love, Joe: The Selected Letters of Joe Brainard, published in November 2024. We excerpted a letter to his lover Keith McDermott, “Showered and shaved, my favorite jeans on, late afternoon in Vermont, drinking a Campari and soda, smoking a cigarette, and writing a letter to YOU. Boy do I feel lucky!”

The opposite of memory isn’t forgetting, it’s never having paid attention at all.

Sarah Moroz interviewed Claire Bishop about her June 2024 book, Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance Today. “I want to be realistic about how the mind works today, which is on multiple streams,” says Bishop, “I think attention’s prioritization of the optical is already waning in favor of alternative modes of being-in-common, reflected in the rise of a discourse of ‘care’ in contemporary art and performance.”

However, my favorite line about attention we published this year comes from Colin Everest who tracked down the two runners depicted in Robert Rauschenberg’s work, Rebus (1955). Everest describes the photographs of the two runners as an anti-clock. “The fanatical attention of two runners to pace has formed an image that, because it rejects any external time-keeping, is paceless,” he says.

There are periods of your life when you have nothing to offer but your attention and that is genuinely humbling. The primary reason I am against scenes is because they function as shortcuts for attention. To my mind, even the briefest gift of human attention is worth a thousand conversations without refusal.

In a truly abundant world, attention will still be scarce because it will force us to love with intention and grieve honestly. Mortality is the final curator––this is not a problem worth solving for.

WORKS CITED

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|