- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Botched pt. 1

Botched pt. 1

What does it mean to be botched?

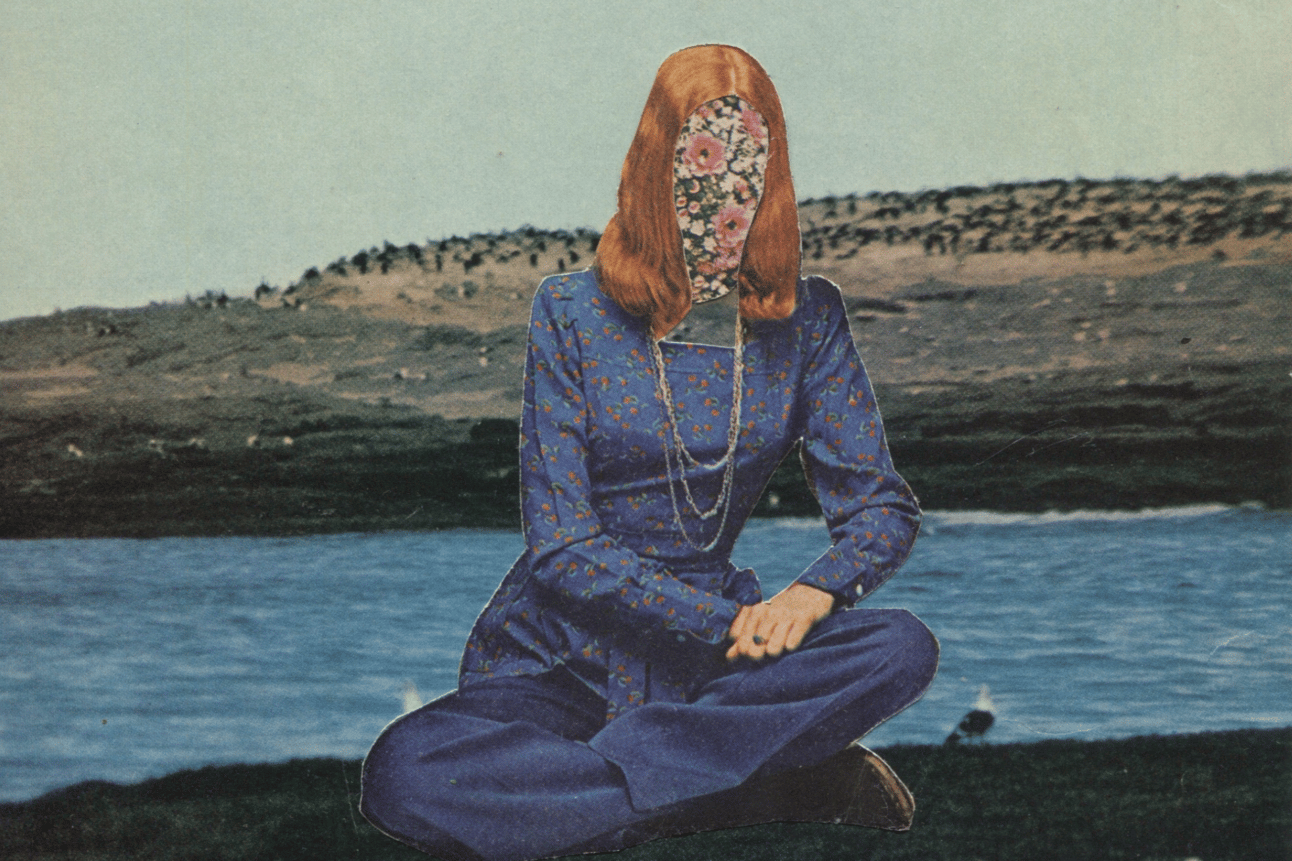

Artwork by Christine Shan Shan Hou

Emmeline Clein on a new social category. This is part one of a two-part series.

In the photo, the woman’s cheeks taper and then swell. A protrusion beneath her lower lip widens her jaw. At first glance, the woman is suffering a classic case of botched plastic surgery, or, depending on what she got done, ‘filler fatigue,’ although she wouldn’t have called it that then. The photo, a mirror selfie, (also a neologism), is from 1928.

The woman in the sepia photo is proto-botched. In the fourteenth century, ‘bocchen’ meant ‘to repair,’ but it also meant ‘to swell up or fester, to bulge’ and by the end of the century the word was being used figuratively to mean ‘a corrupt person; a rotten condition’—presaging the condescension and condemnation people botched by plastic surgery face today. Now, to be botched is to have gone too far in pursuit of beauty capital. But an accusation that someone has gone ‘too far’ is predicated on the assumption that they started off on the right track. In attempting to become the perfect consumers of medicalized femininity many women find themselves on a yellow brick road riddled with land mines. When they end up scarred, they are demonized as vain and self-destructive, deserving of their battle wounds, by the very culture that drafted them into the ‘war on aging’ in the first place.

Now, to be botched is to have gone too far in pursuit of beauty capital.

Decades before the photo was taken, around the turn of the twentieth century, this woman was famous for her beauty. John Singer Sargent painted her. The crown prince of Prussia nursed a crippling crush on her, a Duke left his wife for her. Marcel Proust said he “never saw a girl with such beauty.” But like so many beautiful women she found a flaw in her face and fixated on it, and then she found a scientist with a solution in a syringe. In 1903, at the age of 22, the French-American socialite Gladys Marie Deacon underwent an early version of what is today sold as ‘liquid rhinoplasty’—her nose had a “kink” she hated, which a doctor claimed he could smooth by filling her nose with paraffin wax, one of the first dermal facial fillers.

Like so many doctors before and after him, he took one look at a girl’s face and made some mental measurements. Adjustments, enhancements. She was already beautiful, but perhaps he could perfect her. The filler fell, presaging the migration that would disfigure patients undergoing more modern iterations today, and formed pustules that pressed her skin outwards, transforming her once famously angular jaw into a hilly landscape and disfiguring her lips, which lurched and drooped, lethargic and weighed down with wax. Disfigured, she hid for decades in her mansion, avoiding prying eyes. She bred spaniels and slept with a revolver by her bedside to keep her husband out of the room.

When Deacon had her surgery in 1903, liquid paraffin wax had only been used for cosmetic purposes for a few years, first inserted into skin via syringe in 1899. It was used for breast augmentations and rhinoplasties until 1914, when the practice was abandoned after wide reports of patients afflicted by painful, and in some cases fatal, complications ranging from fistulas, ulceration, and breast flesh necrosis to pulmonary embolism.

By World War II, plastic surgeons had switched to silicone, a tactic first tested on Japanese sex workers living near US military bases. Stolen stocks of silicone from army utility storage were injected into women’s breasts in an attempt to sculpt a supposedly more Western silhouette for soldiers looking for sex. Botox was first formulated as a weapon at Fort Detrick in Maryland. Paraffin itself was a byproduct of petroleum, refined and poured into early tanks. Beauty has long been won on a battlefield. This war, too, is propped up by propaganda, and causes collateral damage—the botched becoming its wounded survivors.

Today, there are highly publicized cases of botching, like supermodel Linda Evangelista’s coolsculpting operation that she claims left her “brutally disfigured,” and almost led to “losing [her] mind.” But the emerging social category of the ‘botched’ doesn’t just belong to celebrities like Evangelista or wealthy socialites—the contemporary Deacons. Rather, regular women, in real pain, seeking solace in Facebook groups and on Reddit forums comprise the majority of this growing population, people navigating lives newly constricted by the very procedures undergone in search of liberation from social reprobation.

These women wanted wider eyes or higher cheekbones or perfectly pursed lips or plump under eyes or unlined necks or triangular chins, or they wanted it all, and what they got was disfigurement to a degree that keeps them home all day in the dark, typing in the blue light of laptop screens.

Artwork by Christine Shan Shan Hou

As the number of people who undergo plastic surgery grows, so too does the number of procedures that go awry or come with unexpected side effects. In turn, the population self-identifying as ‘botched’ grows as well. There are over 80,000 images in the ‘botched’ hashtag on Instagram. On TikTok, videos tagged 'filler fatigue' and 'filler migration' regularly rack up hundreds of thousands of views. In 2023, before these visible metrics were phased out, the TikTok tag for ‘filler fatigue’ had almost a million views, and the associated ‘filler migration’ tag it grew out of had over 83 million.

One dermatologist, speaking to Allure, described a filler fatigued face as “overfilled, doughy,” and “distorted” as a result of too many fillers injected too close together. Filler migrates through the face and can manipulate the movement of facial muscles, causing some to atrophy while others strengthen. The results are uncanny—faces we don’t instinctively recognize as human. The “single, cyborgian” visage deemed “Instagram face” by Jia Tolentino in 2019 is now five years old, but it isn’t aging gracefully, and is instead undergoing strange tectonic shifts as the gel that once sculpted sharp chins and defined cheekbones slides around strangely beneath the skin.

DIRT ON BEAUTY

|

|

|

|

|