- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Botched pt. 2

Botched pt. 2

Pain is beauty.

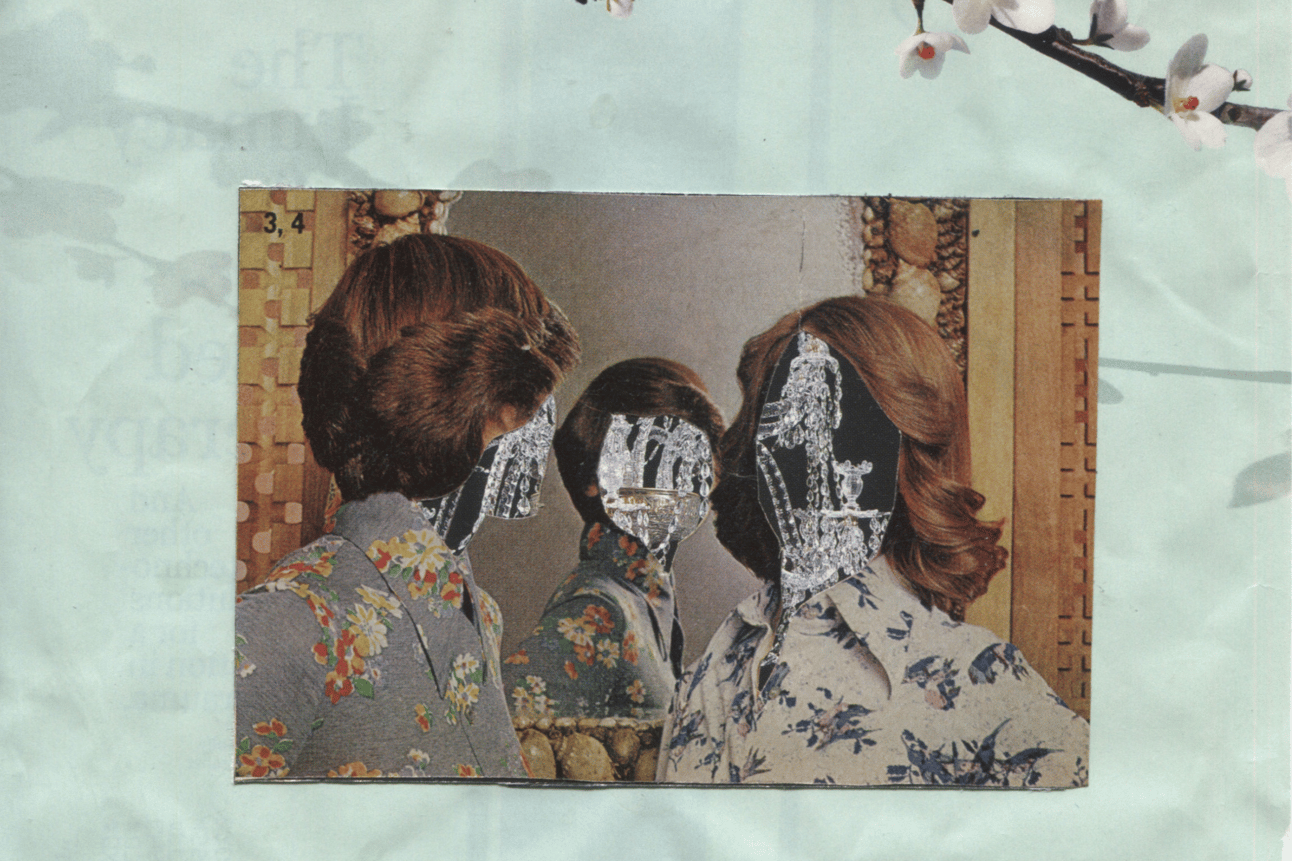

Artwork by Christine Shan Shan Hou

Emmeline Clein on a new social category. This is part two of a two-part series. You can read part one here.

Beauty isn’t just a weapon, it’s also a currency in a cutthroat market. An economic battle as much as a physical one, beauty has its own military industrial complex, interlocking systems of extraction and values, that can seem unshakeable, and attempts to work the system to one’s benefit can easily backfire. “If this is the way the system is I’m gonna get mine,” one 28-year-old woman told me, of her “economically rational decision” to get filler and Botox.

The term “beauty capital” was first popularized in the late nineties, to refer to the economic benefits—salaries, promotions, job offers—a woman gained from being beautiful. Cosmetic body modification, this young woman told me, can feel like an obviously profitable choice in a world where the “return on investment of being beautiful” is sky-high. The language of economics wove its way into the words of almost everyone I spoke to for this essay.

The economic incursion into our sense of aesthetics, not to mention self-worth, is not surprising in our highly branded, financialized world. Writer Danielle Carr wondered, all the way back in 2020, “if the body is not private property to be managed as an investment, then how do we relate to it?”

The ‘botched’ are both unhappy customers and victims of medical malpractice. They represent an emerging social category of disability, which will only continue to grow as our cultural emphasis on youthfulness glorifies surgical intervention. Carr writes that undergirding the rise in cosmetic surgery and noninvasive procedures in this century was the idea that “the patient would be empowered, but with the power of the consumer.” The ‘botched’ are physical manifestations of that lie, purchasing themselves into ever more disfigurement in pursuit of repair, begging the question of whether they were ever broken, and whether understanding our bodies as investment properties is really increasing their value or just dangerously redefining our very notion of what bodies are valued for. In attempting to endow their consumer identity with the power of the patient, the botched illuminate their intersection, one a redditor succinctly defined as “v̶i̶c̶t̶i̶m̶ patient.”

But what does it say that even the art most sympathetic to these women still depicts them as monsters?

The television show Botched premiered in 2014 and is still on the air. As mentioned earlier, the rise in injectable fillers has forged a new form of being botched: one defined by protrusions and swellings, gels swimming up and across skin, faces radically altered alongside lives.

That term ‘filler fatigue’ has edged its way into the beauty discourse over the past few years, as women’s faces started to transform in ways we couldn’t describe using any of the pithy insults already in our repertoire. Beauty micro-influencers suddenly unrecognizable, filming tearful front-facing videos about their botched injections. Celebrities who don’t look their age but also don’t look any age at all, a beautiful woman called out on Twitter for abandoning her ‘birth face’ for ballooning lips and lifted cheekbones, her skin smoothed so all evidence of human life—conversation’s smile lines, thought’s furrowed brow—was excised.

Artwork by Christine Shan Shan Hou

Women are documenting this destruction online and in art, and in that documentation is perhaps a new feminist figure, a botched woman whose survival spotlights the grotesque underside of our beauty standards. But what does it say that even the art most sympathetic to these women still depicts them as monsters?

THIS WEEK IN DIRT

|