- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Our convenient reality

Our convenient reality

A new category of entertainment.

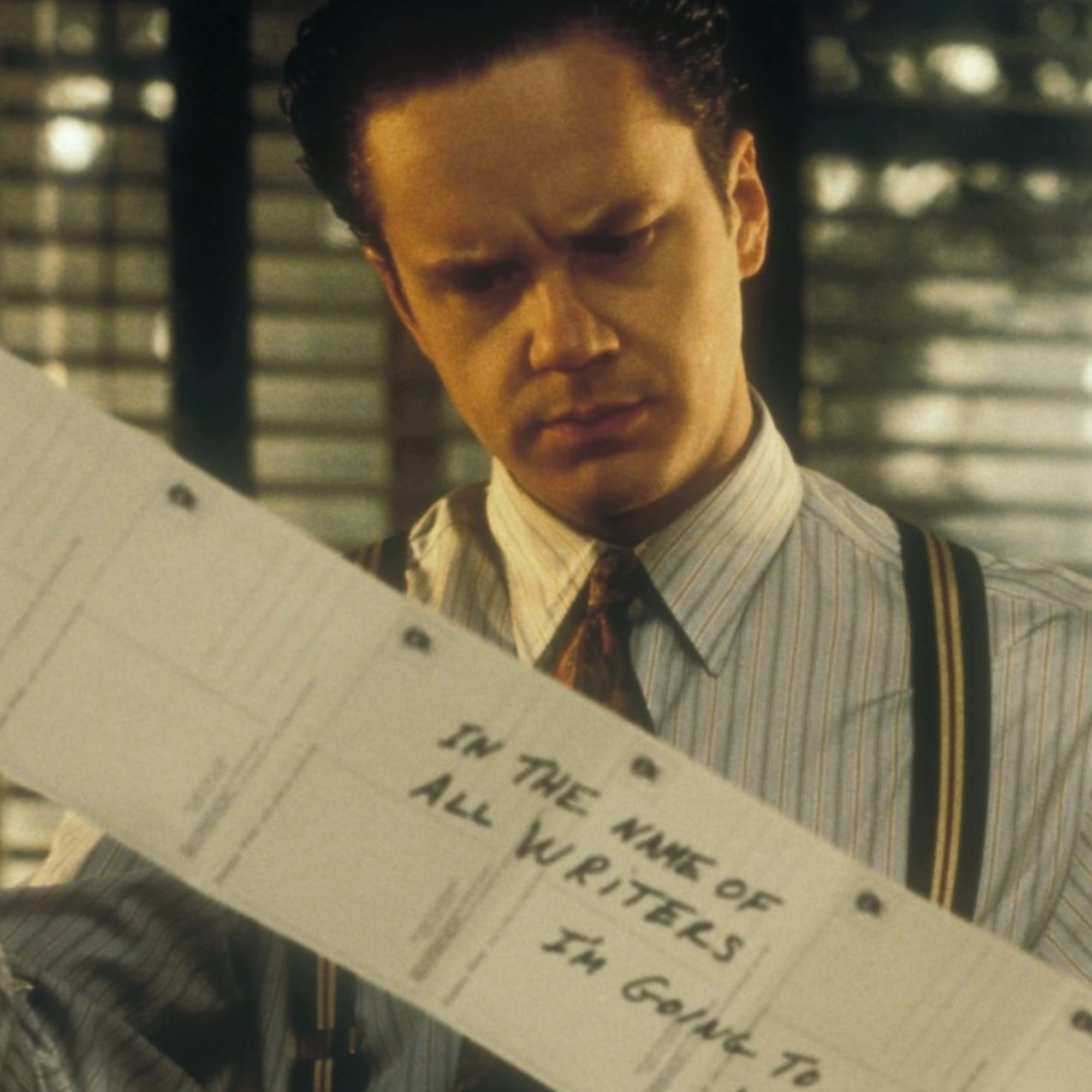

Image Credit: James Marsden in Jury Duty, Amazon Freevee

Conor Truax on what happens when reality shows like KUWTK and metanarratives like Asteroid City converge.

In the finale of The Hills, the reality show about young, wealthy white people in Los Angeles, I watched Brody Jenner and Kristin Cavallari say farewell. I watched them drive off in a convertible, and I watched them wave goodbye to people whose reality I’d consumed for 102 episodes, without them having any reciprocal knowledge of mine. Except as they turned their backs to one another, they turned their backs to me, too. The camera panned out slowly, revealing that the whole finale was being filmed in a studio lot. It had all happened, but was any of it real? Or had I just spent fifty-one hours in a dream…

I experienced a similar feeling watching any series in The Real Housewives universe, whose first series promised raw insight into a flamboyant life with the slogan “I live my life in HD: sharp, bright and more focused than ever." The perennial promise of reality television as an entertainment category is that what we are watching is real, or, at least happening in the infinite present, without the same narrative design and emotional manipulation of scripted stories. However, in major cities, onlookers have claimed that Real Housewives cast members act as if they're on set, with directors pausing dialogue and asking the women to repeat, alter, or rehearse their lines. The slogan begins to take on a new meaning. As the women’s popularity grows, so too does their sphere of influence outside the show, and when their scandals follow them offscreen, there is total confusion as to what is manufactured or not.

This is not unique to the Real Housewives franchise. Take, for example, Kim Kardashian’s 2011 marriage to NBA-player Kris Humphries. The first season of the spin-off series Kourtney and Kim Take New York followed Kim in her budding romance with Kris, a then-player for the Nets. Within months, the pair got engaged, and between the first and second season the pair broadcasted their wedding as a four-hour special that broke E!’s viewership records at the time. Famously, Kim announced their divorce after seventy-two days, months before the show’s second season aired. This prompted massive backlash and calls to cancel the show. Viewers felt deceived and manipulated by the months-long PR-blitz promoting the nuptials, while the showrunners felt this outcry was a point of further leverage. The second season of the show focused on building a redemptive arc for Kim by vilifying her ex-husband, and shortly thereafter, Kim got together with Kanye. The deception was soon forgotten by everyone except for Kris Humphries, whose lawyers doggedly pursued an annulment of the marriage on the basis that it had been a fraudulent attempt to (successfully) boost show ratings.

SPONSORED BY JOGGY

Want to boost your energy and focus levels without negative side effects? Joggy is the new clean energy brand you need to know about.

Most energy drinks and supplements contain synthetic ingredients or excessive levels of caffeine, leaving you feeling wired, jittery and crashing once the effects wear off. Joggy is changing the game with a range of better-for-you energy products that leave you feeling on top of the world + ready to take on your day—whether that's breaking your PR or crushing a work deadline.

Though these products were designed to support you pre and post-activity, you can take them whenever you need a boost of energy that lasts.

Head over to getjoggy.com to learn more and shop from their line of clean energy essentials. Plus, Joggy is offering Dirt readers 15% off. Use the code DIRT at checkout to score the discount.

Separate from so-called reality television, we have metanarratives, which have grown in stature since The Matrix in the late 90’s, to recent films like Barbie and Asteroid City. Metanarrative is a category of entertainment that uses a form of self-conscious storytelling to draw attention to a story’s own artificiality by referencing aspects of our shared “reality” to portray itself as “reality,” too.

I reference reality in quotations because in our digitally-mediated world, reality—yours and mine—has become subject to the forces of editing, omission, and confused cause and effect, as virtual sleights of hand become so convincing so as to be totally obscured. Culture continues to reflect social reality, but more and more social reality has begun to reflect culture, and now, it seems as if people are interested in meta-reality not only for the pleasure of its passive enjoyment. I suspect it’s because the viewer becomes, in a sense, an accomplice to the events transpiring on screen, parasocially linked and economically tied to a production and its characters. The audience is encouraged to think like an author, rather than sit on the sidelines as a passive viewer, whether or not they are truly given the chance to write anything at all.

The viewer becomes, in a sense, an accomplice to the events transpiring on screen, parasocially linked and economically tied to a production and its characters.

Filmic metanarratives found mainstream popularity beginning in the late 90’s with blockbusters like The Matrix and eXistenZ, and are now everywhere: from American Fiction to Midnight in Paris to High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, and Riverdale. These projects know that we’re smart viewers, and ensure that they treat us as such, with a humored self-referential acknowledgement of their facts and fictions that viewers can treat as a game. And even if reality shows are not explicitly a metanarrative, they have spurred a trend of meta-narrative discourse amongst viewers on TikTok and Reddit who convene to differentiate the real from the fake, the good from the evil, all the while conforming to the designed engagement filmed and preened to draw them in.

“Meta-authors” create narratives that grant us the feeling that while the world is being manipulated, it can be explained, and because we are smart, we can understand it too. We get to be in on the secrets of the world, even if that world is a fictitious one like Zion in The Matrix. Of course, this is by design, making metanarratives no different in their manipulation than those forms that came before it. In fact, it’s more manipulative by virtue of the deceit of its deceit.

Didactic metanarratives are the worst offenders in this domain. Take, for example, the Marvel films, which bask in a self-referential humor that acknowledges their own consumerist popularity (e.g., Iron Man’s commodification), all while using the humor to become more consumerist, more popular, through the recycled packaging of good versus evil morality tales that connect viewers to any number of realities that are not their own.

FURTHER READING

|

|

|

|

|