- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

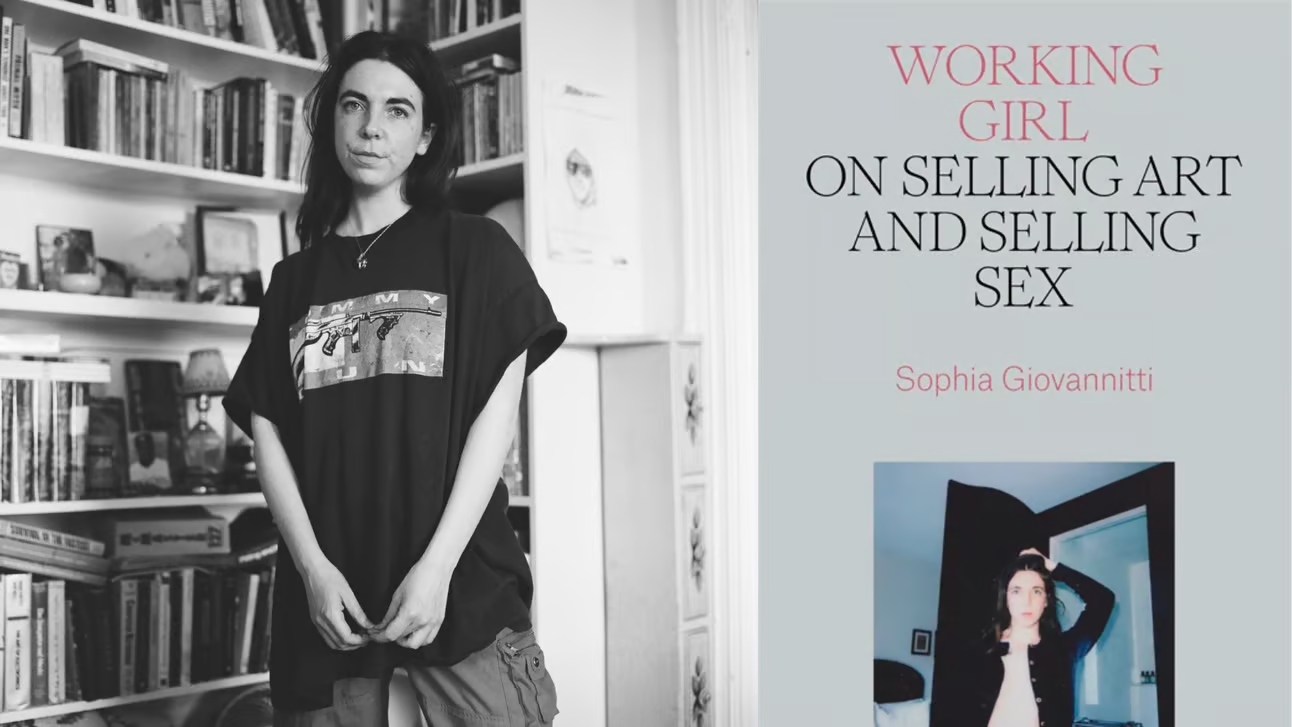

- Cyborg Nostalgia

Cyborg Nostalgia

Whither cyberpunk?

Teknolust (2002), courtesy of MUBI

Terry Nguyen asks: how did AI—science fiction’s infamous dystopian boogeyman—become cringe? This essay first ran on Vague Blue.

Last summer, the Criterion Channel released a timely line-up of films about artificial intelligence. The programming then coincided with a lot of paranoia about the future of art and AI—paranoia that has, for better and worse, subsided as tech companies raced to incorporate AI into their existing suite of products, normalizing its novelty among users who previously found it suspect.

With Apple’s latest AI announcement, I’ve been thinking about how we’ve become inured to, or even bored by, the concept of AI, even as its rapid developments raise concerns about digital privacy, surveillance, and intellectual property. How did AI—science fiction’s infamous dystopian boogeyman—become cringe?

How did AI—science fiction’s infamous dystopian boogeyman—become cringe?

The earliest films in the Criterion Collection are from the 1970s and surprisingly goofy. The one exception is Demon Seed (1977), a bizarre, Cronenberg-lite movie about a woman who is taken hostage in her own home by Proteus, an AI computer program developed by her husband. Proteus plans to impregnate the woman to bear a cyborg child so that it can achieve a “complete” form—its intelligence “alive in human flesh,” capable of touching the world.

The film’s premise loosely reminded me of Titane (2021), Julia Ducournau’s body-horror flick about an on-the-run serial killer who consummates with cars. I like Titane for its boldness—how Ducournau infuses touching moments of hope into the protagonist’s deprived world, culminating with the birth of her mutant child. On the contrary, Demon Seed ends on a note of haunting resignation, as its characters bask in the inevitability of catastrophe. Humans are quick to dismiss a computer, Proteus says, but less so another human. Its cyborg heir, which seems to be a fleshly vessel for Proteus itself, won’t be so easily ignored.

I like Titane for its boldness—how Ducournau infuses touching moments of hope into the protagonist’s deprived world…

I love watching older movies about cyborgs and AI even if, as Demon Seed proves, they aren’t very good. There’s an icky, tactile pleasure to seeing how a film like David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) tries to anthropomorphize a machine, rejecting the slick, immersive smoothness so characteristic of modern devices for an aesthetics of abjection, representative of “the new flesh.” This staid smoothness is ubiquitous in contemporary films about AI; Her (2013), After Yang (2021), and AfrAId (2024) all follow characters whose lives are affected (or in AfrAId’s case, upended) by the AI assistants they’ve purchased. Yet, the design of their homes and workplaces are so clearly influenced by contemporary aesthetics to communicate a visual parallel between the films’ reality and ours.

Blade Runner 2046 (2017) is a rare exception to the polished Apple Store minimalism that is a pervasive and “radically unsexy” blight on our visual culture. Of the sartorial choices in Her, Stella Bugbee writes, “The clothing feels stunted by a culture that has stopped thinking about fashion. When you live so much in your own imagination, communicating through screens and ear pieces, who needs innovative clothes?”

The cyborg is a hybrid species, a “condensed image,” a post-human subject born from the dregs of rapid industrialization.

Article continues below

SPONSORED BY SYMPHONY

Your All-in-One Music Marketing Solution

SymphonyOS is the go-to platform for independent artists, offering AI-driven tools to automate social media ads, fan tracking, and website building. Save time, grow your audience, and focus on creating music while SymphonyOS takes care of your marketing needs effortlessly.

The same could be said about the cybernetic body in contemporary AI films—once an uncanny territory rife for exploration and exploitation. The cyborg is a hybrid species, a “condensed image,” a post-human subject born from the dregs of rapid industrialization. Older films exemplify this paranoia of a parasitic technology invading and infesting people’s bodies and bloodstream, a fear that feels quite old-fashioned, as our relationship to computers has veered towards symbiosis. Nowadays, it’s common to think of our phones as a prosthesis—a second brain, a second eye—that is so seamlessly “integrated” into our daily activities that it is no longer a separate, unruly entity, but a portal to our social selves.

The cyborgs in these newer films, if they take forms outside of cyberspace, are deceptively human-looking—a sign of the futurism in After Yang, Blade Runner 2046, and Subservience (2024). Cyborgs either “pass” as humans or their existence is siloed within an unremarkably small, transportable device. While said to be “intelligent,” their world-view is seemingly either limited to what their owners show them or programmed to wreak havoc on their lives. The “sentience” of an AI like Her’s Samantha or Blade Runner’s Joi appears to be wholly disentangled from the complex cybernetic web that powers her, as her “humanity” is emphasized over her non-human capabilities.

While these films explore relevant questions about technology and humanity, there is little sense of the imaginative “other-ness” that is palpable in vintage AI and cyborg flicks like Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), which features a Japanese salaryman grotesquely transforming into a metal cyborg (complete with a drill dick), or Teknolust (2002), where a bio-geneticist named Rosetta Stone (Tilda Swinton) utilizes her DNA to breed three live, self-replicating AI cyborgs. While watching Teknolust earlier this week, it occurred to me that perhaps the evolving visual representation of cyborgs and AI (in Hollywood, at least) reflects the gradual dismantling of the computer’s physicality.

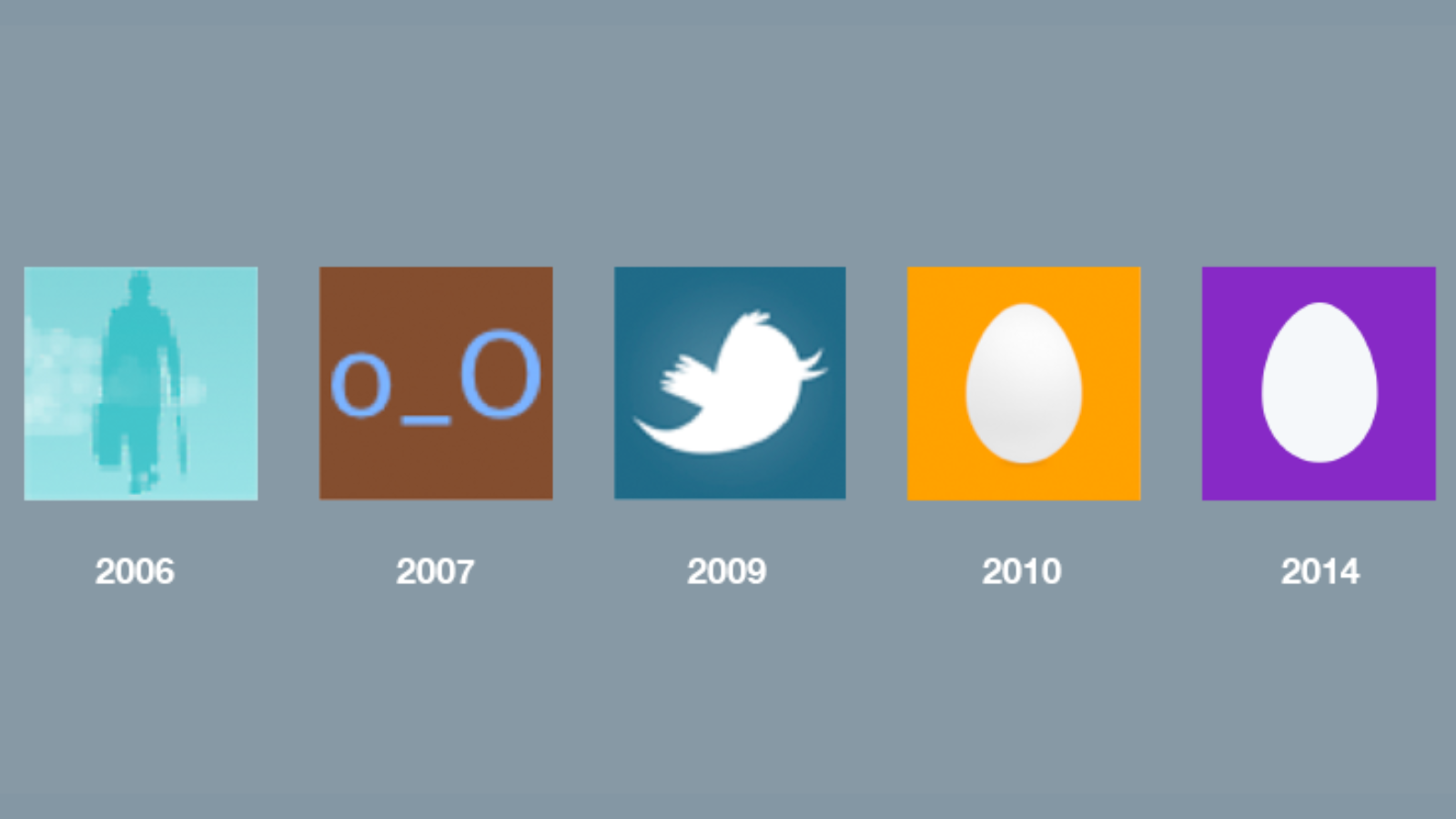

Major developments in consumer hardware have stalled since the advent of the iPhone. The paper-thin screen is everywhere, its design and interface characterized by this prevailing smoothness. New devices have fewer and fewer ports, and with wireless charging and bluetooth headsets, there is diminishing use for cords and cables. User preference has shifted towards smaller solid-state drives (SSDs) rather than hard disc drives (HDDs)—the black box that I grew up calling the computer’s “heart.” (I used to think the screen was its “brain,” although I’ve long lost the logic of the analogy.) We’ve succumbed to the unyielding tide of software that is eating the world, abandoning our unwieldy attachments to hardware. The boundary between the physical and the virtual are more porous than ever, and software masks the extent of this cybernetic world and reinforces this sense of hyperreality.

The characters in Her and After Yang exist in a world much like our own: AI is a commonplace technology that warrants little surprise or skepticism.

The characters in Her and After Yang exist in a world much like our own: AI is a commonplace technology that warrants little surprise or skepticism. Even the set designs feel oddly sanitized, as if imported from a nearby Apple Store. These movies revel in the emotional core of human-machine relationships, positioning the alien as something like us—a human without a body who is capable of feeling. (Chris Weitz’s AfrAId and S.K. Dale’s Subservience are poor attempts that more recently have tried to buck this trend, featuring rogue AI assistants that try to impose their will upon a hapless human family.) Yet, the shift from horror and fear to relational empathy is compelling, and imbues Her and After Yang with pathos, evoking a melodramatic depth that is often lost in the older, campier works about AI.

Still, I wonder what we lose when we “humanize” the cyborg from its cyberpunk roots, remaking its body after our own image, or into a body-less voice. I long for the unruly physicality of the tentacular computer in Tetsuo or the video-game whimsy of Teknolust—movies that are arguably about love as much as they are about the fear of the unknown. Perhaps the boredom we feel towards AI is more towards the narrow applications promoted by the tech giants: AI as a productivity tool, as a skills substitute for creative workers. What can we learn from these arguably dated visions of the future? And how can we, as the filmmaker Asuka Lin writes, develop “an evolved language for the masses, speaking of the marginalized body and psyche in relation to this modern age of techno-hegemony”?

MORE BY TERRY NGUYEN

|

|

|

|

|