- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

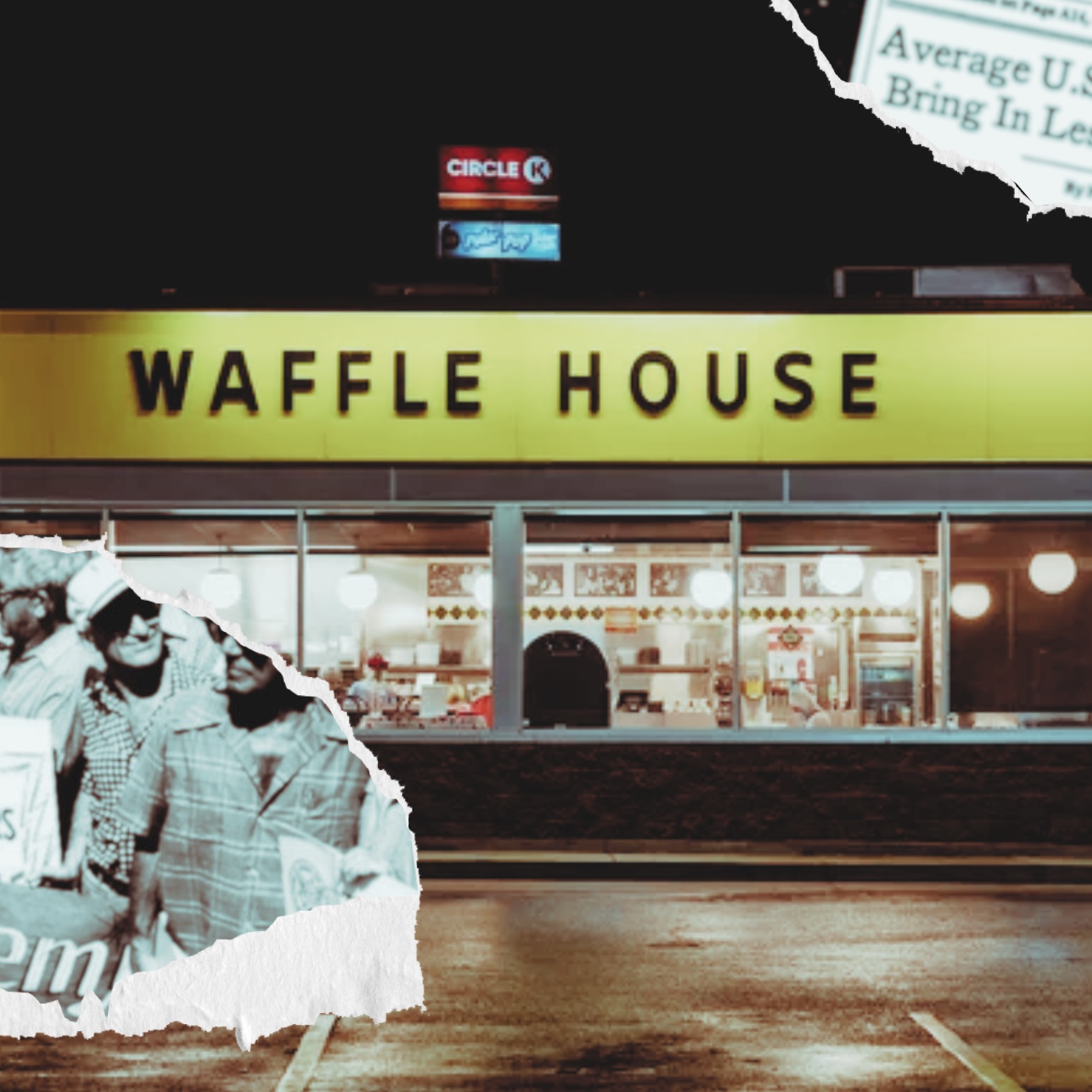

- Disassociating in a whale costume under the Texas sun

Disassociating in a whale costume under the Texas sun

"I learned quickly that people accept what you tell them if you say it cheerfully."

Artwork by Sharanya Durvasula

Brittany Leitner on how she got out and the whales didn't.

This story was the runner-up in our “the way we work” essay contest in collaboration with Lux. This story was co-published and supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project’s James Ledbetter Fund.

To feel any semblance of air pass through the whale costume, I could only rock my arms up and down in a thrusting movement. Unfortunately to park-goers, this action looked like I was dry-humping the air. But the slightest puff of relief that passed through the black mesh-lined mouthpiece to hit my obscured face was worth it. It felt like heaven. Sometimes I’d attempt to step as I humped, so it looked less like a mid-air gyrate and more like a zany whale dance. But most of the time, I did it unabashedly; my 20-year-old manager chastising me was a small price to pay for the glorious bout of air that fanned the beads of sweat.

Sometimes I’d attempt to step as I humped, so it looked less like a mid-air gyrate and more like a zany whale dance.

Exiting an air-conditioned dressing room into the San Antonio summer heat felt like opening the door to a 400-degree oven and climbing inside with your frozen pizza. Underneath a 20-pound polyester whale costume, it was like experiencing hell in real time, only survivable because we were stationed outside in 30-minute increments. All of the suffering would, eventually, end. And when it did, my grey t-shirt would be soaked through under the weight belt I was required to wear while in costume. Beneath the black nylon caps we wore to keep hair out of our eyes, my hair was matted to my skull.

When my manager mentioned my air-humping in front of guests, I looked her square in the eye and said sincerely, “Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry. I would never do that if I realized how it came off.” That appeased her. From then on, I only humped when I knew she was out of eye-shot. I was at the park every day the summer I turned eighteen, working forty hours a week and dumping each paycheck into a secret account my parents knew nothing about. I had made the mistake of clueing Mom into my finances at my last job, only for her to drain my account so she could make rent. At eighteen, I was escaping my parents' grip.

In early 2009, the minimum wage in Texas was $6.55 an hour. By July of that year, it would increase to $7.25 to match new federal standards, while I—barely out of high school—got paid $10.25 an hour to work in my whale costume at SeaWorld. It was nearly four dollars above the absolute bare minimum the state of Texas was allowed to pay a human being. In other words, I couldn’t believe my luck. Recruiters had visited the school gym to drop off flyers during my varsity dance team practice. The boys’ locker room received visits from Army and Air Force pushers; the girls got SeaWorld. I took the bait.

The boys’ locker room received visits from Army and Air Force pushers; the girls got SeaWorld. I took the bait.

SeaWorld anchors my high school memories, but still, the years blur. I know now that forgetting is a way to survive. During my four years of high school, my family and I drifted in and out of homelessness. We inhabited and were evicted from duplexes, apartments, and rental houses. I learned quickly what an envelope taped to the front door meant; how we’d have to spot clean a home just before we left it to avoid charges from the landlord. Sometimes my sister and I lived with friends while my parents went to… where did they go? Once, we packed into the spare bedrooms of someone my dad met at his retail job selling electronics. Another time we paid by the week at a motel with two full beds and a small kitchenette.

Once we were staying in a motel right next to SeaWorld when I entered the elevator in my uniform and met a family who had flown in from out of town. They had come all this way just to see the famous whales in person, so they were excited to talk to me. They also wondered what a park employee was doing at their motel. I was always ready with an excuse. When friends picked me up from new locations, I’d say it was my aunt’s house, a cousin’s house, or a temporary stay while we got our plumbing fixed.

“My apartment is being remodeled!” I said in the upbeat park voice I used to talk to children. “Have fun at the park today!”

I learned quickly that people accept what you tell them if you say it cheerfully. I also learned that if I spoke like nothing was wrong, my body believed it. At the park, concealed under costume, I could disassociate from the reality at home. I was just another teenager working a summer job, laughing and complaining about the heat like everyone else. I had been acting in my real life for so long. Now I was finally getting paid for it.

The park felt more empowering than my first job as a cashier at a greeting card store, where I earned minimum wage and had to contend with creepy men complimenting me or asking me out. Never mind that I was sixteen. One day, a man said he would wait outside in his car all day for me to be done with my shift. He said he’d come back for me and take me away to give me a good life. I knew by then that men caused more problems than they solved, thinking of my dad, whose verbal abuse was more consistent than his employment.

But inside the steely gates of the park, men exhibited their best behavior. Why? Visiting was a special occasion, one that cost about $80 per person—before the popcorn buckets, chili cheese fries, and refillable souvenir soda cups. Men typically didn’t come to SeaWorld alone, but with families. Even when I wasn’t in costume, I was free to be my confident, gregarious self without getting asked for my number or followed around. I directed guests to the dolphin tank and restrooms with the grace of a flight attendant flagging exit doors. And I loved every minute of it. This artificial utopia devoid of openly lecherous men did wonders for my ability to disassociate even further. My shoulders somehow relaxed under the weight of my 20-pound costume.

How dehumanizing it is to shell out $10 for a sandwich when you’re only making $6.55 in the hour you get to eat it—if you get a paid lunch break at all.

The park offered something else I hadn’t experienced at my card-hawking job: perks like free uniforms, so I didn’t have to spend money before making any. SeaWorld demanded I wear white sneakers so they gave me a pair. They had an employee canteen where I could get chicken tenders, fries, and a drink for $3.25—my daily diet that summer. I could avoid meal prepping at “home” during the times I didn’t have a kitchen, or avoid being around Dad in the common area of the kitchen when we did have one. How dehumanizing it is to shell out $10 for a sandwich when you’re only making $6.55 in the hour you get to eat it—if you get a paid lunch break at all. Why weren’t all jobs like this?

THE WAY WE WORK

|