Daniel Kolitz on grief and the uniqure aura of flip phone photography.

It was a Monday morning and I was ghostwriting a promotional blog post about cybersecurity. I was typing out phrases like in this unprecedented threat environment. I was typing out phrases like full visibility into internal systems. I was even typing out phrases like dynamic, scalable, cloud-native architecture. I was typing out these phrases and I was thinking: Jon is dead. I typed: exploitable vulnerabilities. I thought: dead. I typed: AI-enhanced detection tools perfectly suited to the needs of the cloud-first modern enterprise. I thought: I am losing my fucking mind. I wrote an email to the client, something like: sorry, my friend died, going to need a few more hours on this. It was too much to share, I wasn't thinking straight. The client replied promptly. They said: No problem!

I'd learned the news from Zach an hour earlier. A group text to a few of us from the old high school gang. Had our lives gone according to plan—the plan as it existed ca. 2008—the text would have been unnecessary: he could’ve just called a meeting of the enormous mansion we all lived in together. But he wouldn't have needed to call a meeting because—had things gone according to plan—Jon would not have died. Except Jon had died, Jon was, somehow, dead, and our once freakishly insular group—a group with its own private language, sacred rituals, commemorative holidays—had not been a functioning concern since the tail end of Bush II. I had not spoken to Zach, or Jon for that matter, in at least seven years.

Home that night, done with typing if not thinking, I was not excessively well. I spoke to Zach on the phone: he's a corporate lawyer now, I learned, with a kid on the way. Who knew. A few hours later, he texted me: Kolitz, I deleted my Facebook... do you still have access to all those phone picture albums from high school?

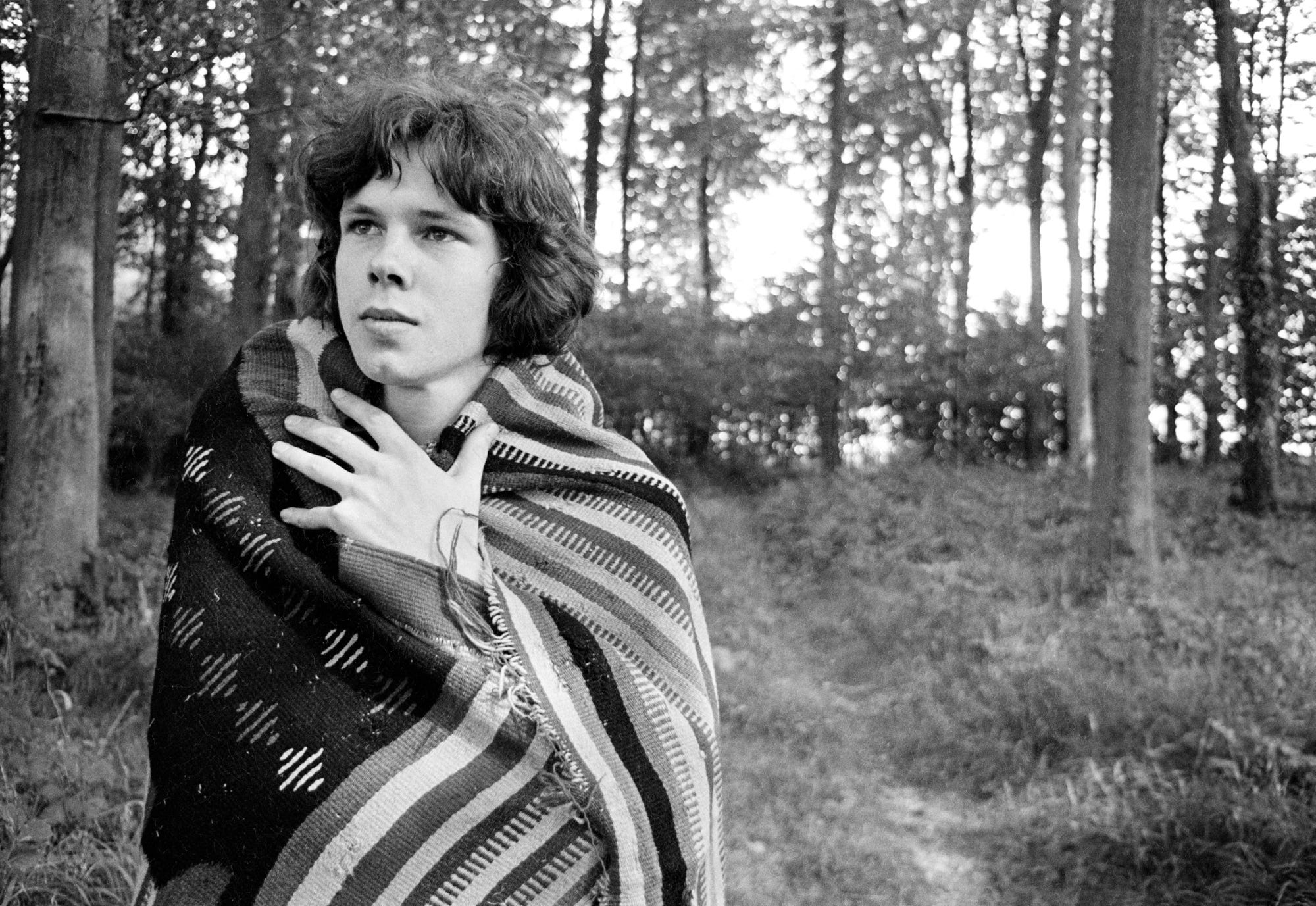

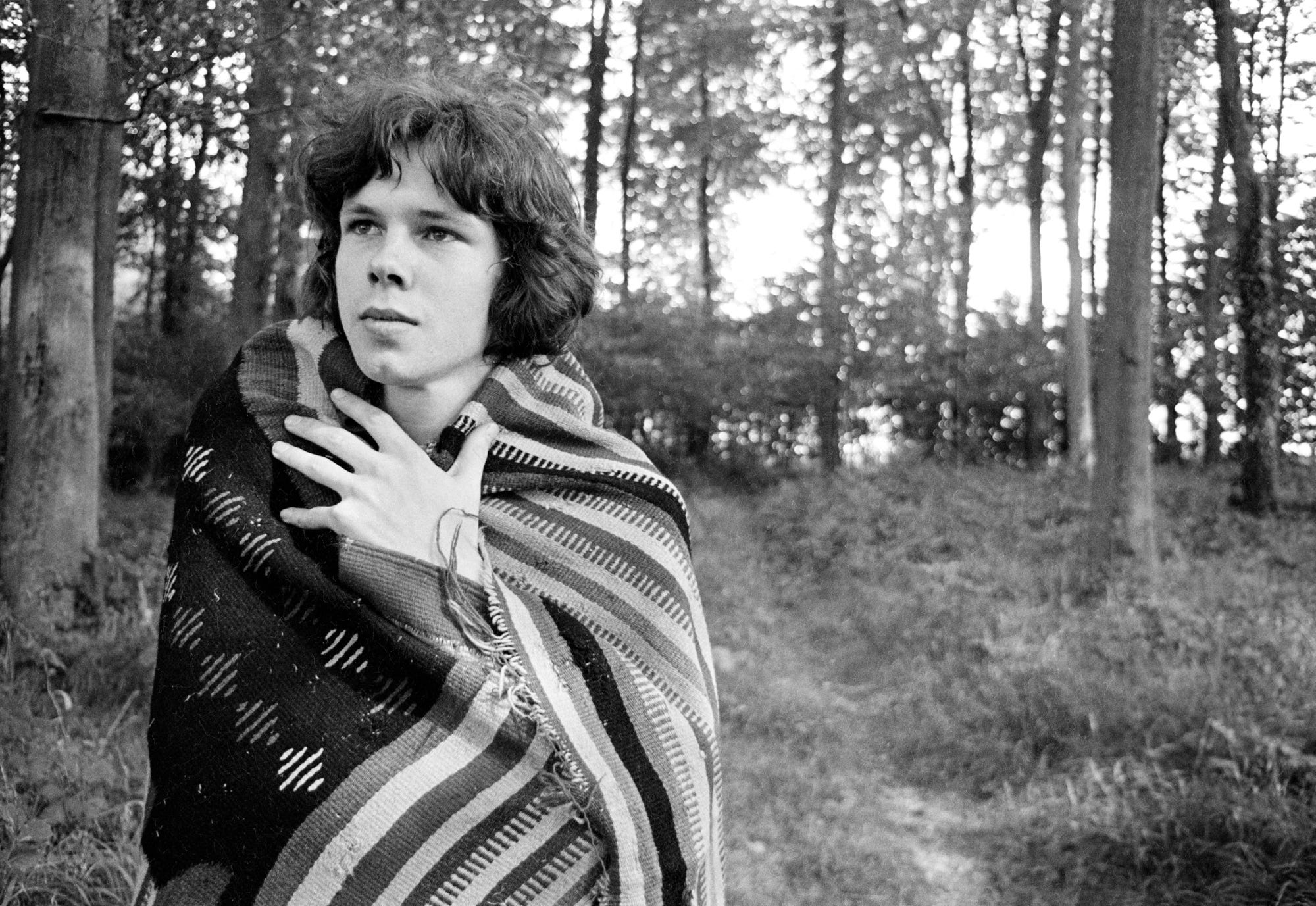

The pictures! I had to check. I checked. There they all were. Let me explain. In high school I was a straight-C student, except for gym, which I failed outright (twice). I had no extracurriculars. If someone had told me to think hard about my future career prospects—and someone must have, at some point—I would simply have thought: no. At sixteen, seventeen, I lived for my friends, and the pictures were a part of that. I took them with my flip phone and uploaded them to my PC with a special cable I bought from the Cingular store. From there I posted them to Facebook, in thrice-yearly installments. They were supposed to be candid: my friends would make a little game of trying to catch me in the act. I'd made the albums private shortly after graduating high school but that night I imported them—all 800—to a Google Photos folder, which I shared with the gang, or what was left of it, via text.

Over the next few days, when I should have been ghostwriting promotional blog posts about cybersecurity, I found myself instead looking at the pictures. Cognizant of the fact that they depicted my own literal childhood, I nonetheless came to feel they were significant. Not their content, per se—mostly teens in hoodies getting high in parking lots—but definitely their form. I started to think about the lo-res flip phone photograph as a cultural artifact: its distinct qualities, its place in the history of consumer picture-taking. Possibly I was thinking about these things to avoid thinking about certain other, more pressing things, but regardless all this thinking led me to a single conclusion: the flip phone photograph, as an object of study, has been sorely neglected.

| Dec 20, 2023 Consider the periwinkle. |

| Aug 30, 2023 Television’s shortcut to complexity. |

|

|  | Apr 14, 2023 |

|

|  | Nov 16, 2023 |

|

|  | Aug 5, 2022 |

|

|  | Aug 14, 2023 |

|

|  | Jan 27, 2023 |

|

|  | Oct 31, 2022 |

|