- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Going over the line

Going over the line

“I'm the same kind of writer.”

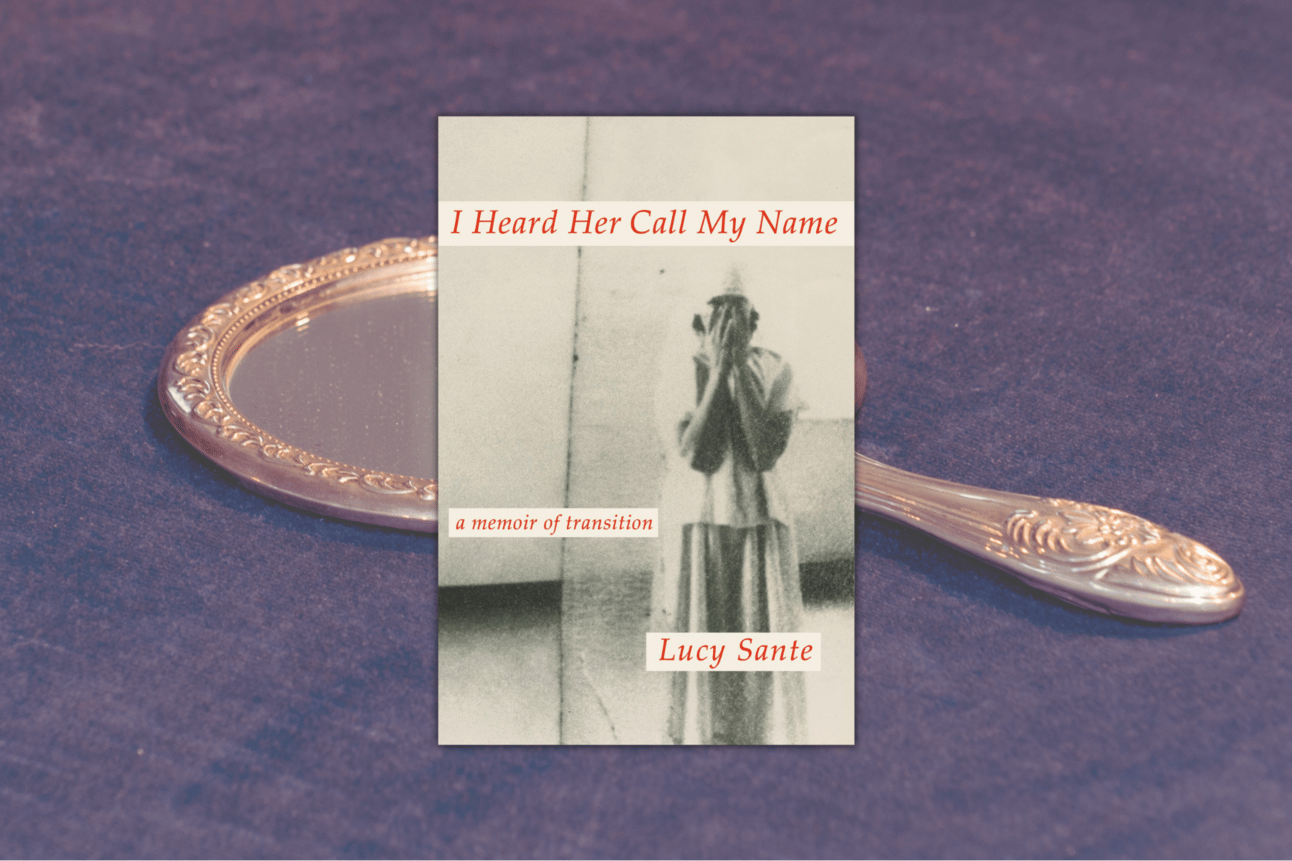

Chris Randle and Lucy Sante discuss Sante’s new memoir of transition.

Wander long enough through New York’s Strand bookshop, where the writer Lucy Sante once worked, and you will find a copy of her 1991 historical portrait Low Life, like the Bible waiting inside a motel room. Published under the subtitle Lures and Snares of Old New York, Low Life maps Manhattan’s landscape before the skyscrapers: rat-baiters, nickelodeons, Tammany fixers, roaming bohemian enclaves, gangsters called Girl Face or Spanish Louie. For somebody raised on the flavorless rations of official Canadian literature, reading Low Life years ago unpicked a lock. Sante had a poet’s sense of rhythm and the crime novelist’s instinct for disaster. Her prose moves like the lightbulb swinging above a derelict stairwell.

Sante had a poet’s sense of rhythm and the crime novelist’s instinct for disaster.

Sante grew up in New Jersey as the only child of working-class Belgian immigrants. She skipped town via Jesuit school (Regis, Upper East Side). One timeline of her new memoir I Heard Her Call My Name describes her youth in 1970s New York, a hyena kingdom built atop ruins. She spent the days, such as they were, at The New York Review of Books, going from mailroom to editorial; later on she would dance to Billie Holiday records at Elizabeth Hardwick’s place, or go to parties with a Basquiat painting staring back from the refrigerator door. Left unspoken, sometimes even to herself, was the desire she’d repressed since childhood, to be a woman. “I was, as ever, in fear of that one inadvertent step that would take me across the line,” Sante recalls, “never to return.” The other half of I Heard Her Call My Name describes what happens after she crossed the threshold.

Her coming-out post went up on Instagram in September 2021; Sante mentioned eggs cracking, a phrase coined by trans women decades younger that fits her sensibility perfectly. I was astonished not by the news but by her illustrating smile. In I Heard Her Call My Name, Sante caricatures the gloomier male persona she felt obliged to create: “saturnine, cerebral, a bit remote, a bit owlish, possibly ‘quirky,’ coming very close to asexual despite my best intentions.” And yet her memoir suggests that this performance came out of deeply held tastes, even though a tyrannical director controlled it. She’d been cast in the wrong role. Sante arrives at certain truths about deception, the poses we fashion, the bricolage we call a self. “So many things about my new being felt familiar,” she writes, “as if I were remembering them.”

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Chris Randle: You were initially asked to write about transition by an editor you knew at Vanity Fair, right? When did you decide to expand that into the book?

Lucy Sante: Well, first of all, I came out on Instagram in September 2021, and within a couple of days I had four offers to write my story. And I went with Vanity Fair because I like [editor] David Friend, and because I thought I might get a glam photo shoot out of it, which I did, amazingly. Although they didn't bring me any clothes, I had to use my own clothes. But, to tell you the truth, the minute I hit on the idea, like the second day after my egg initially cracked in February 2021, I had the idea of running all these pictures from my past—I ran every photograph of me taken between the ages of 11 and the present [through FaceApp]. Not that many, because I've never encouraged people to take my picture, but that was so immediately compelling, I knew that I was going to write a book, and that these pictures were going in that book. So the book preceded the piece, although the piece was fantastically helpful.

CR: You also say in the book, even aside from you personally, that people just didn't have many photographs of themselves back then. And I thought it was interesting to begin with you feeding those dozens of photos into FaceApp, because you've written about photography a lot, but never in the context of yourself. I was looking at Evidence—the book, not the abstract concept—and at one point you write, "If photographs are supposed to freeze time, these [crime photos] crystallize what is already frozen." I'm wondering, what was it like writing about photos of yourself? Did they unthaw frozen time?

LS: Yeah, they did. It was spectacular. The AI was very interesting. Sometimes it would return shots that were like, what the fuck am I looking at? Smears or grotesques, missing part of the face. But then when it did hit, it was like it was reading my mind. "That's how I would've worn my hair." A timeline of my life that was going on in my head. It was like the AI had peered into the deepest recesses of my brain to come up with these images.

CR: Elsewhere in the book you write about Nan Goldin, who's been taking beautiful photographs of her trans friends for half a century now, and how that casual intimacy gave you a terror of recognition. What do you see in those photos now?

LS: Gosh. I felt this deep envy, and recognition that I couldn't penetrate that world. I mean, I'm thinking especially of the first pictures I was aware of, which were her Boston pictures. It was strange too, because the women in those pictures—Kenny Angelo was already butch by the time I saw the pictures. And David Armstrong never really dressed up, except once or twice. There's a stunning picture of him. By the way, I only recently found out that David Armstrong and I were born the same day the same year. I wish I'd known that when he was still alive. But anyway, when she was doing the early slideshows at the OP Screening Room on Broadway in the early '80s, she was showing those pictures.

Later, after my friend Janice Stein moved out, Greer Lankton became Nan's roommate, but that was after our week or whatever it was of dating. Greer scared the shit out of me, frankly. She was this nice person who made this incredible art, these astonishing dolls, but I was just terrified. I thought, I come into contact with this person, I'm going over the line. I was terrified of that, always. I was terrified of having this epiphany like the one I actually did have, you know? I thought it would come, and I wanted to forestall it by any means necessary.

I was terrified of having this epiphany like the one I actually did have, you know? I thought it would come, and I wanted to forestall it by any means necessary.

CR: What you said about your reaction to Greer, I think in the book you describe it as something that happened out of repression. And in your previous memoir The Factory of Facts, you begin with a sort of Oulipean gambit where you daydream a bunch of fantastical life stories, like, evading the subject. Was the relative directness of I Heard Her Call My Name a reaction against that?

LS: Well, it wasn't a reaction against that. That particular thing in Factory was a one-time gambit. It was just a wild idea that came into my head one day, it wasn't meant as a philosophical position. It was all imagining possible outcomes of this crisis my family faced in 1959, because I was thinking a lot about historical hinges, and the biggest hinge in my life, really, is that moment where my parents had to decide what to do [whether to stay in America or go back to Belgium], when I was a very small child. And the directness of this one is because it's a subject I have to be direct about. Also, frankly, people keep asking me, "Have you noticed any changes in your writing since you've transitioned?" Yes and no. I'm the same kind of writer, I use words the same way, I have the same stock of general knowledge. The big difference is—it's not directly from the transition, it's a side effect. It's the fact I have no secrets left. And that means I have no fucks to give. I am completely frank and rather blunt about everything. Maybe too much [laughs].

CR: And it's interesting because there's still ambivalences, you know? I really love how you open with the big coming-out email, but then you also include the second email, your unsent retraction. That's built into the structure of the book itself, this contrapuntal timeline, moving back and forth, so things overlap. What led you to go in that direction?

LS: It was a simple architectural solution to a problem, which is that I have two stories to tell, and one of them is the transition, at least the first six months of transition, which is when the fireworks went off. And so I had that story, which takes six months, and then I had the whole background, because you do need to know who I am to be able to measure this transitional moment. That's 66 years, so what order do I play them in? And that's impossible. One version could be the classic magazine journalism, where you're in media res big drama, and then you pull back. But I thought alternating was much more interesting. It's a gimmick. It's from suspense novels. You keep interrupting actions with other actions and it builds up suspense artificially, as it were, so it aids in the propulsion of the narrative.

I have no secrets left. And that means I have no fucks to give.

CR: It also dovetails with one of my favorite lines from the book, "Transitioning really makes you appreciate the beauty of dialectics." I know you are extremely not a Twitter person, but that would be a good Twitter shitpost [both laugh]. So like, I love archives, I think that was part of what initially drew me to your work, because I grew up being fed these Canadian warhorses like Robertson Davies, and the idea that you didn't have to write stodgy novels, that you could pursue your obsessions instead...being a haunter of archives, I suppose. How does that change when the archive is your own life? Not just all those old photos, but there's the old newspaper clipping where they captioned you as Lucy...

LS: I love archives too. I love being a detective, I love putting together clues. And I maintain my own archive with a certain degree of fidelity, but as I detail in the book, the trouble is that I've been denied so much of my archive by people destroying major parts of it. My mother throwing away, oh God—I'd rescued some of the stuff from my childhood, but my mother threw away all my teenage stuff, which really, really hurts. And then my first wife threw away all my clothes that weren't suitable for going to Odeon in. My aunt, my father's sister, threw away—didn't throw away, burned—all the family papers, and I know so little about my father's family, that just killed me. Over and over: Losses from the big move in 1959, crates being smashed. So my archive is fragmentary, which probably is actually good from a literary point of view, because there's nothing worse than having too much information. It forces you to go a little farther in piecing things together.

I had this memory, because writing this book kicked up all this memory shit from the past, and I was remembering how, during the mourning period for my grandmother, this is Belgium in 1962, there weren't funeral homes. My grandmother died in our house, and was lying in state in the front parlor for three days. I said goodbye to her before I went to school. But there were all these relatives coming in and out of the house, and partly because I was shy, a little afraid—there were all the scary country people coming in [laughs], I was a little terrified of my peasant relatives—I went up to the attic and I found the trunks with my grandparents's things. That was my introduction to sepia-toned photography from the past. Photographs from before World War I. It was a classic thing where it laid an egg in my head, which hatched some 30-40 years later. So I've always been drawn to that stuff, and it's always my crutch when writing.

THE BOOKSHELF

|

|

|

|

|