- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Lifestyle pt. 1

Lifestyle pt. 1

Creation, consumption and curation.

Image Credit: Ed Costello, Flickr

Daisy Alioto traces the origins of a concept that has come to define our lives online. This essay was originally self-published in 2020.

Read the introduction here.

Picture a doorway on an ordinary street in Vienna. On one side is a building services company and on the other, a concept restaurant and store selling wine and flowers. Wired street lights cross overhead. Beside the doorway is a plaque: In Diesem Hause Lebte Und Wirkte Dr. Alfred Adler Begründer Der Individualpsychologie. “In this house lived and worked Alfred Adler, the founder of individual psychology.”

It is a typical Central European apartment building, white stone with six stories and a gray roof. From above, the neighborhood has the pastel hues of tennis pitch. You might lean forward in your seat as your plane approaches the city to take it in among a cluster of anonymous red roofs, but could easily overlook it on foot. Even with the historical marker, the doorway does not hold the same allure as Prater’s romantic ferris wheel or the yellow Schönbrunn Palace, daffodil of the Habsburg empire.

Image Credit: Unhashtag Vienna

In 2018, beleaguered by social media-fueled tourism of the city’s most popular sites, the Vienna Tourist Board launched their ‘Unhashtag Vienna’ campaign. Signs at Vienna International Airport proclaimed “Welcome to Vienna. Not #Vienna” and for three days a replica of Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss overlaid with a red hashtag hung in the Belvedere. (Not willing to truly upset their guests, the museum kept the original in the next room.) “Today everything exists to end in a photograph,” Susan Sontag wrote in her collected essays On Photography. “A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it—by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir.”

When I was 10, my family went to Disney World for the first time. My parents saved for the trip by putting coins in an old pasta sauce jar that still smelled vaguely of Ragù. The Disney resort we would stay at sent us a video about the parks, and in my excitement I watched it over and over again. Now, when I am looking forward to a trip I search for photos that other travelers have posted online–their memories fueling my anticipation.

Travel photography has become a part of that vague corner of media known as lifestyle content. On social media, photographs signify the lifestyle of the person who posts them. But the concept of lifestyle isn’t limited to its depiction. In order to understand the meaning of lifestyle, one must go back nearly a hundred years to that nondescript doorway in Vienna.

In 1995, Robert K. Merton and Alan Wolfe published a paper about the incorporation of sociological terms into the popular press. At the top of their list was the word “lifestyle,” which was used 106,607 times in the press between 1991 and 1993. In a distant second was the term “role model,” at 27,054 times. The authors attributed the word ‘lifestyle’ to psychologist Alfred Adler and sociologist Max Weber. “Newspapers have their business sections, which, of course, use terminology from economics, but they also have their lifestyle sections, which use terminology from sociology,” Merton and Wolfe wrote. Even in the early 90s, the idea that lifestyle content could be anything but lifestyle was unimaginable. Now, the categories of lifestyle content are infinite: wellness, eco, VSCO, vegan, minimalist, maximalist, Marxist, to name a few.

Florence Knoll Bassett and Eero Saarinen in 1957. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Alfred Adler was credited with the first use of lifestyle in 1929. Although the term was used by Max Weber in 1922, his writings would not be published in English until after Adler’s. In his book The Science of Living Adler writes, “A pine tree growing in the valley grows differently from one on top of a mountain. The same kind of tree has two distinct life styles. Its style on top of the mountain is different from its style when growing in the valley. The life style of a tree is the individual expression of a tree moulding itself to its environment.” According to Adler, a person’s lifestyle is established in their earliest years of life: their sense of inferiority or superiority, security in relationships and means of striving towards a life goal. Like the tree in the analogy above, this lifestyle is revealed as a person moves through different environments. One might say this is an internalized view of lifestyle.

By comparison, Weber’s sociological definition of lifestyle is an external one. Weber writes that classes are stratified by their relationship to the means of production, while status groups are organized by consumption of goods, aka lifestyle. One’s lifestyle is determined by one’s life chances, basically economic, and hence the overlap between class and status.

In the mid-century, “lifestyle” replaced “style of life” in the general lexicon. Changes in marketing practices around the same time gave Americans a narrative view of lifestyle. As Merton and Wolfe noted, just as words are exported from sociology to the popular press, methodologies are co-opted as well. Marketers began to use focus groups that relied on psychological knowledge (from Adler) to reach conclusions about status (Weber). Ironically, these surveys and quantitative insights became increasingly important to interpret the litany of lifestyle images bombarding the public on a daily basis.

A 2007 article in the Journal of Marketing explains a method of consumer research derived from individual psychology called EM (earliest memory) in which subjects are asked individually and in groups to describe their earliest memory of a product. “EMs operate as a projective technique based on the errors that are inherent in the memory retrieval process. The focus is on patients’ recollections of specific incidents that occur before the age of ten. To keep their memory stories coherent, people fill in the missing parts of the stories that their memories cannot finish. They project themselves–personality and lifestyle preferences–into their EMs.”

In 2011, archaeologist Ian Hodder wrote, “It is accepted that human existence and human social life depend on material things.” At the Turkish archeological site that Hodder leads, skeletons are buried under the dwellings in which they once lived, making it possible to determine which households lived the longest in the emerging ‘house society’ of the neolithic period. “We can find no evidence that the long-lasting houses controlled production or exchange or had better resources in some way. Rather, once they had successfully started to build a history and to amass evidence of that history (skulls, bucrania, body parts, images of feasts), these houses were able to elaborate on and perform that history more powerfully than others.”

I wrote above that Adler’s definition of lifestyle is internal, while Weber’s is external– but obviously things are not that simple. The same external childhood factors that influence psychology also form the prototype for consumer consciousness later in life. Therefore, lifestyle as performance is both an internalized and externalized practice. This is apparent in the latest definition of lifestyle on Business Dictionary dot com: “A way of living of individuals, families (households), and societies, which they manifest in coping with their physical, psychological, social, and economic environments on a day-to-day basis.”

If lifestyle as a pattern of thought and behavior and lifestyle as a matter of consumer taste were once separate, they are now one. The contemporary definition of lifestyle is propped up by the unprecedented visibility of things on social media, making individual consumption more public than ever before. In the words of Mark Fisher, “The thing about capitalism is that it provides things that nobody likes.” But the sticking point of capitalism is that people like things quite a lot.

Hodder’s research advances evidence that survival of the fittest doesn’t just depend on biology, but rather a meaningful relationship to things, irrespective of Weber’s definition of class (control of production). The fact that capitalism now sells lifestyle to us as a narrative exercise (based on our own personal narrative!) does not negate the fact that lifestyle was a communal proposition long before it was a personal brand. The communal history of lifestyle gives me hope that we have free will in material accumulation: lifestyle as a way of coping with capitalism, as well as the object dependence that is intrinsic to civilization. We tell ourselves stories in order to lifestyle.

We tell ourselves stories in order to lifestyle.

“As humans we are involved in a dance with things that cannot be stopped, since we are only human through things,” says Hodder. We will continue to perform lifestyles made possible by the Internet whether individual social media platforms survive or not, and even, especially, if we log off for good. Social media altered the world in the same way that the white cube changed galleries. Just seeing objects depicted there legitimized them as something one could desire. This is how we got from Proust’s madeleine to avocado toast.

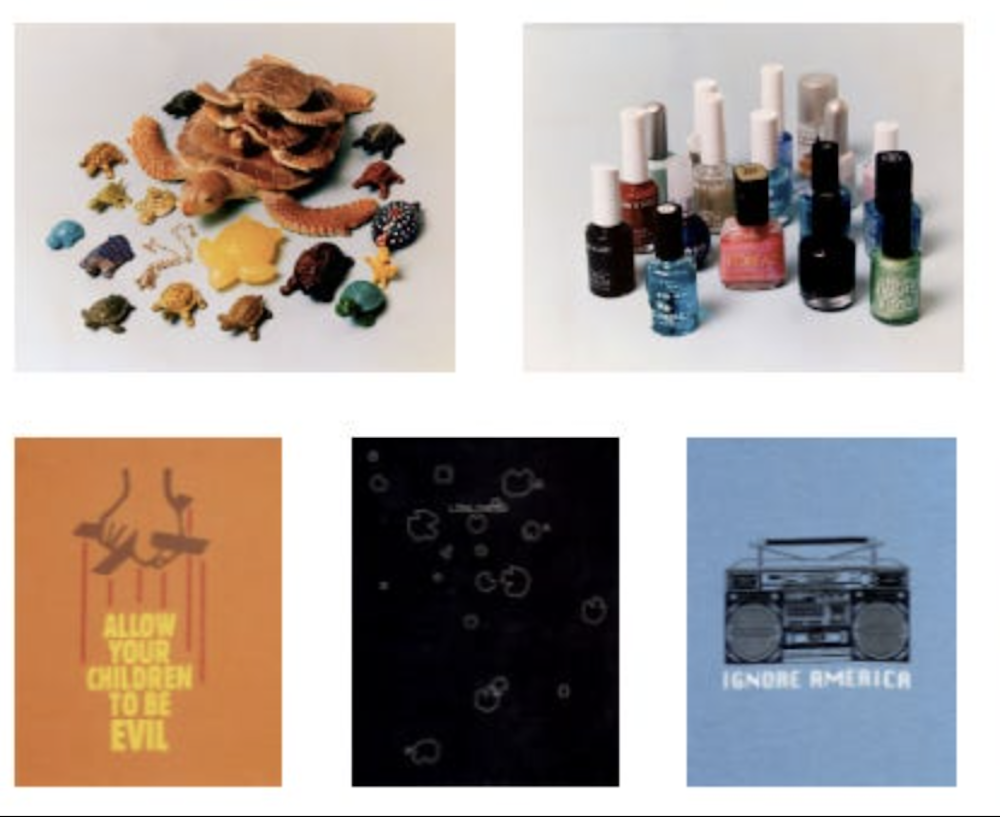

Contemporary lifestyle is a cycle of creation, consumption and curation. A thing is created when we ascribe meaning to it. It is consumed when we assign a value to it. It is curated when we tell a story about it. This semiotic loop also applies to the performance of lifestyle itself. A lifestyle is created when it is described. It is consumed when it is shared. It is curated when it is received.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

|

|

|

|

|

|

|