- Magazine Dirt

- Posts

- Lifestyle pt. 2

Lifestyle pt. 2

Slouching towards storage.

Ansel Adams, Trees with Snow on Branches, "Half Dome, Apple Orchard, Yosemite," California, Courtesy of National Archives

An excerpt from “What Is Lifestyle?”

Daisy Alioto traces the origins of a concept that has come to define our lives online. This essay was originally self-published in 2020.

Read the introduction here.

In 1891, the first household moving business in America opened in Sioux City, Iowa, relying on horse and wagon. The founders were brothers Martin and John Bekins and they soon expanded to warehouse storage as well. If you want to know how the American lifestyle was created, the Bekins family is a great place to start. During the Gold Rush, they assisted would-be prospectors in moving their possessions out West. They then stored the excess furniture that came with the Gilded Age and helped the new monied classes move into their second homes. Bekins became a Los Angeles fixture during Hollywood’s heyday by storing, cleaning and distributing film. In the early 1970s, they even made national headlines because Daniel Ellsberg was storing the Pentagon Papers in their facilities.

This is how the Los Angeles Times described Bekins’ California footprint in 1989: “They rise like medieval castle keeps above busy Southern California intersections. Their steep blank sides, relieved by rows of small windows, give no clue to the activities behind their fortress-like walls. Only the skyline signs reading Bekins Storage reveal the mundane purpose of these muscular architectural landmarks.”

In other areas of the country, storage as architecture can be glimpsed from the highway, or as billboards advertising self-storage (or in the water towers that sometimes make their way into fine art photography). Storage is marketed as aggressively as the stuff we put in it. The French Aristocracy Never Saw It Coming Either reads one particularly memorable Manhattan Mini Storage campaign. Storage is sold with the promise of the best thing most of us can hope for: some stability, even as the boom markets that sold us all that stuff would just as easily take it away.

Today, there are more self-storage facilities in the United States than McDonald’s and Starbucks locations combined. Storage in the cloud, however distant it may seem, corresponds to data centers that are filled with more stuff. The Bekins company is a shadow of its former empire, but the instincts it capitalized on are alive and well. The millennial may stream Tidying Up with Marie Kondo on Netflix, but they don’t get rid of stuff–they simply redistribute it. The human lifestyle is perpetually slouching towards storage.

The human lifestyle is perpetually slouching towards storage.

The storage business was essential to creating the American lifestyle because it allowed for the movement and accumulation of things. However, the depiction of lifestyle owes a debt to public and private forms of media, images that give things value.

In college, I interned at ELLE magazine in the Time-Life building. My days began with a train ride from Westchester. I padded through Grand Central, along 42nd street and took a right on 6th avenue–past Bryant Park and the gleaming white facade of the Grace Building. I still had a flip phone, so any deviation from this memorized path seemed impossible. (Now my days are dominated by grids. I dream about them.)

The aptly named LIFE magazine was launched by Henry Luce in 1936 just one year before Edwin H. Land founded the Polaroid Corporation. Land is famous for saying, “You always start with a fantasy.”

When LIFE was founded, it was the first American news magazine entirely focused on photojournalism. In a way, Luce did start with a fantasy, the fantasy of a world defined by images. Some of LIFE’s most iconic photographs dealt with both the American dream and its dissolution. LIFE photographer Gordon Parks, born in 1912, began as a photographer for the Farm Security Administration and went on to live in Paris and shoot haute couture. His career spanned the definition of lifestyle as psychological adaptation and personal consumption. He also pioneered depictions of the Black family.

In 1967, Parks profiled the Fontenelle family in Harlem. The readers of LIFE were appalled by the family’s living conditions and sent in money to support them. Parks wrote about their bleak lifestyle in his memoirs: “The family faces a world of gloom, hunger and a thousand little violences every day.” However, Parks himself was an American success story. He writes, “I desperately wanted [my] children to escape the hardships I had. As they grew I made sure their pleasures grew.” He bought his son two horses and his daughter a baby grand piano. He built a pool for his wife and a private tennis court. His children attended private schools.

The Time-Life building, in addition to being the backdrop for my internship, was the setting for three seasons of Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men. Lauded for its dedication to midcentury modern detail, the show includes plenty of furniture by Florence Knoll–whose interiors for the CBS office (designed in 1964) set the new standard for an era of corporate lobbies curated to advertise the lifestyle of those that passed through them. T-shaped furniture legs, oblong conference tables and white rooms accented in primary colors can all be traced back to Florence Knoll. She also embraced right angles and grids, which are de rigueur on contemporary websites and social networks.

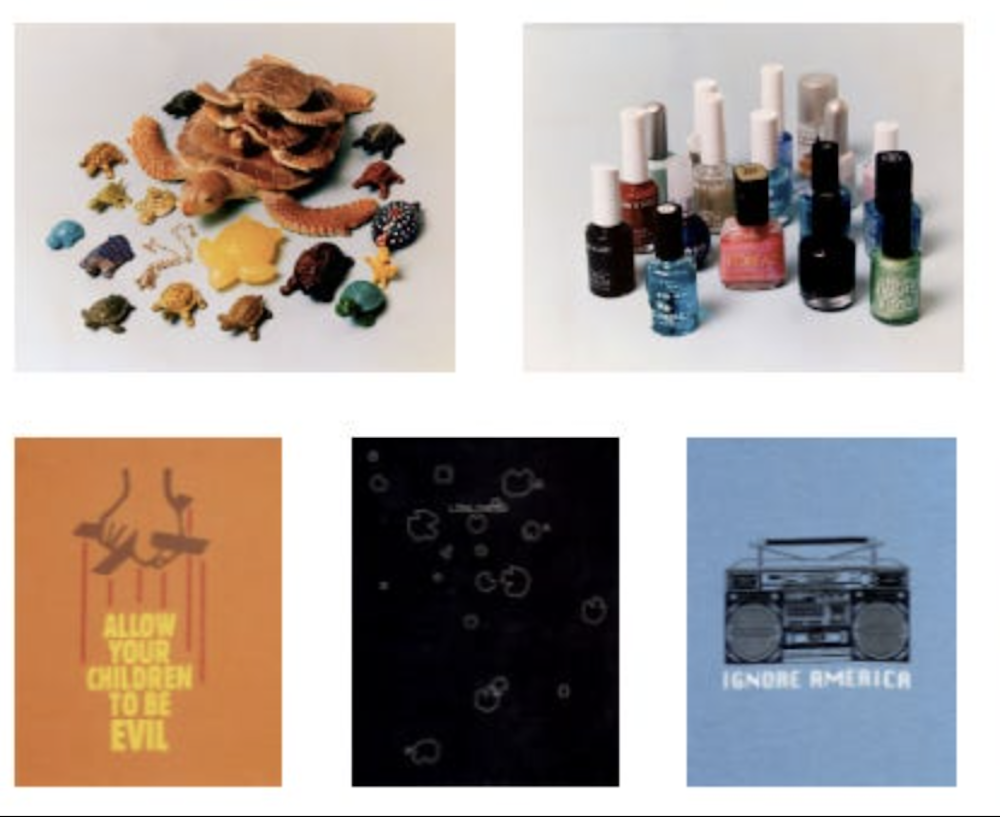

In 1987, Andrew Kromelow was working as a custodian in Frank Gehry’s California studio when he began to arrange his tools at right angles. In tribute to the Florence Knoll furniture he admired, Kromelow called this practice ‘knolling.’ In 2009, Kromelow’s friend Tom Sachs–who also spent time in Frank Gehry’s shop–adopted ‘knolling’ into the motto of his own studio with the abbreviation ABK: Always Be Knolling. Unlike Kromelow, Sachs documented this practice with overhead photographs. This style of photography, objects shot from above, is known as the “flat lay”. It is now ubiquitous in lifestyle media.

John Berger writes, “The special qualities of oil painting lent themselves to a special system of conventions for representing the visible. The sum total of these conventions is the way of seeing invented by oil painting,” including the ability to possess valuable objects through their still life depiction. Knolling and the flat lay represent another way of seeing that is unique to digital life: using the ownership and consumption of objects as a visual representation of the self. It’s the new still life.

Knoll may have influenced the Instagram grid, but Edwin H. Land gave us the surrounding white space. Around 1943, Land went for a walk in the Santa Fe desert with his daughter, Jennifer. He took pictures of the 3-year-old, as one does on vacation, and she asked “Why can’t I see the picture now?” According to company lore, that question touched off years of experimentation which ended with the introduction of the first Polaroid camera in 1948. The white border surrounding each photo was added later to conceal the pouch of chemicals needed for the snapshot to develop.

This is how we got from Proust’s madeleine to avocado toast.

Today, the impetus behind the Polaroid is exactly how lifestyle is consumed: with immediacy. Not to mention a concern for authenticity. Steve Jobs called Land “a national treasure” in Playboy and the rainbow-colored Mac logo is an echo of Polaroid packaging. Lifestyle content used to be top down, trickling from magazine photographers like Parks to consumers. Today, personal photographs enabled by Land dominate on technology created by Jobs.

The only type of hoarding that isn’t pathologized by capitalism is money, but there is no limit to the number of images we can create, consume and curate. When I want to revisit my past personal taste, I turn to old photographs and social media posts. It’s increasingly difficult to disentangle images from memories, and concerning, given Adler’s definition: “(A person's) memories are the reminders she carries about with her of her limitations and of the meanings of events. There are no 'chance' memories. Out of the incalculable number of impressions that an individual receives, she chooses to remember only those which she considers, however dimly, to have a bearing on her problems.”

There are no chance photographs on my iPhone either.

MORE LIFESTYLE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|