Shirt by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren

Katy Kelleher on the controversial history of bringing the asylum to the runway.

When the Quakers first started using the penitentiary system in the late 1700s, it was hailed by some as a radically humane––perhaps, even dangerously progressive institution. Even though the cells were tiny and the inhabitants had to wear terrifying masks, even though they had no human contact and quickly went mad, even though the model was a total failure, it was still preferable to the alternative. Instead of hanging for one’s crimes, you could sit quietly and think.

We still haven’t figured out what to do with humans who do bad things, either to themselves or to others. At our worst, we punish. At our best, we attempt to reform and aid. But mostly, we just default to containing and restraining.

Like those early prisons, the straitjacket wasn’t intended as a torture device, but a direct route to greater bodily freedom. Instead of chaining mentally ill people to walls, they could get swaddled up in canvas and amble around the yard! They could breathe in fresh air. They could hug their chests while staring at the sky—an improvement over iron links, certainly.

Freedom and restraint are two concepts that exist in tandem, strange bedfellows made stranger by our fantastic capacity for perversion. From the start, the straitjacket had a sexual side. Even before Houdini began titillating the public with his wriggling and writhing, the constrictive garment had a certain voyeuristic appeal. To see someone in a straitjacket was similar to catching sight of someone in stocks—it rendered the constrained person vulnerable in a very particular way.

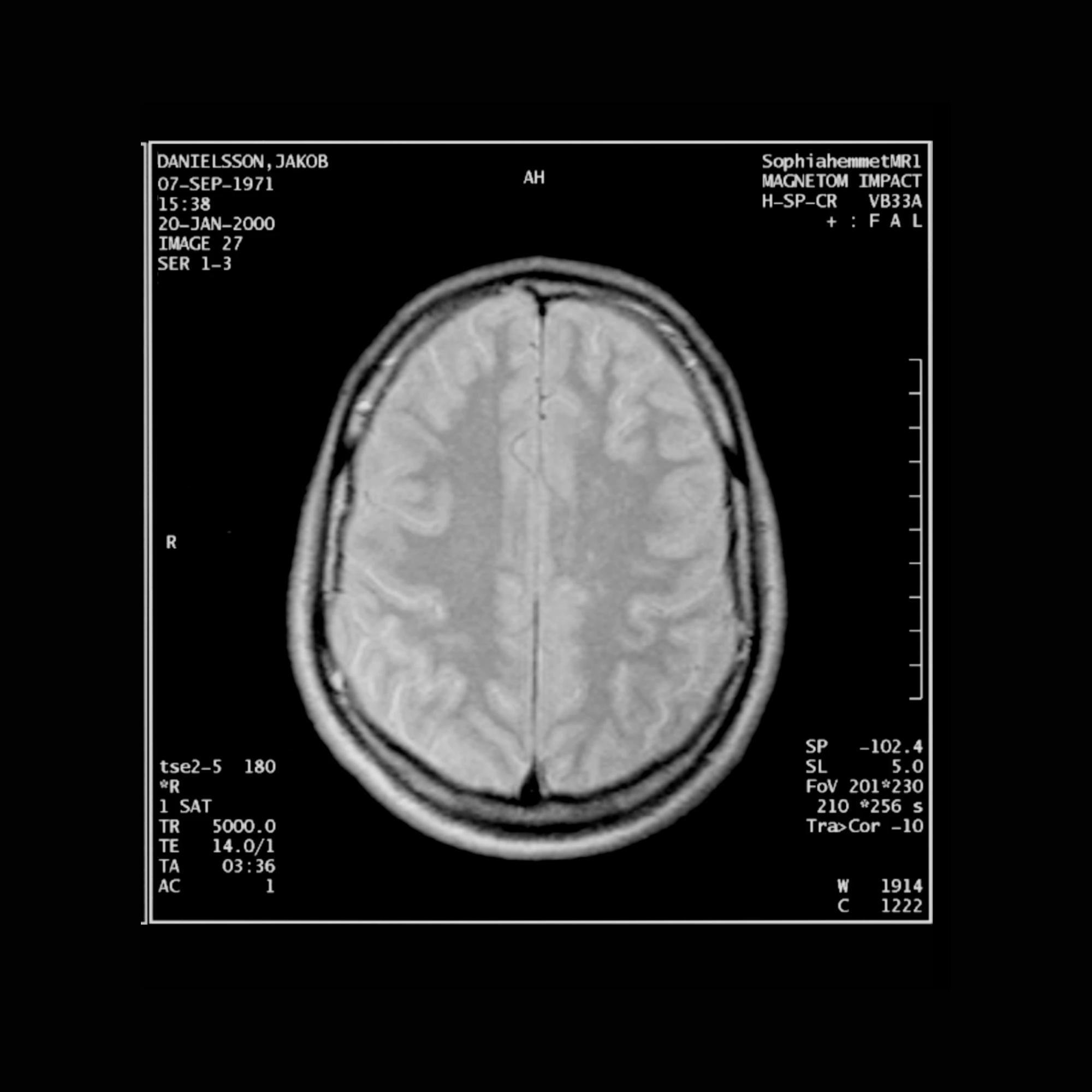

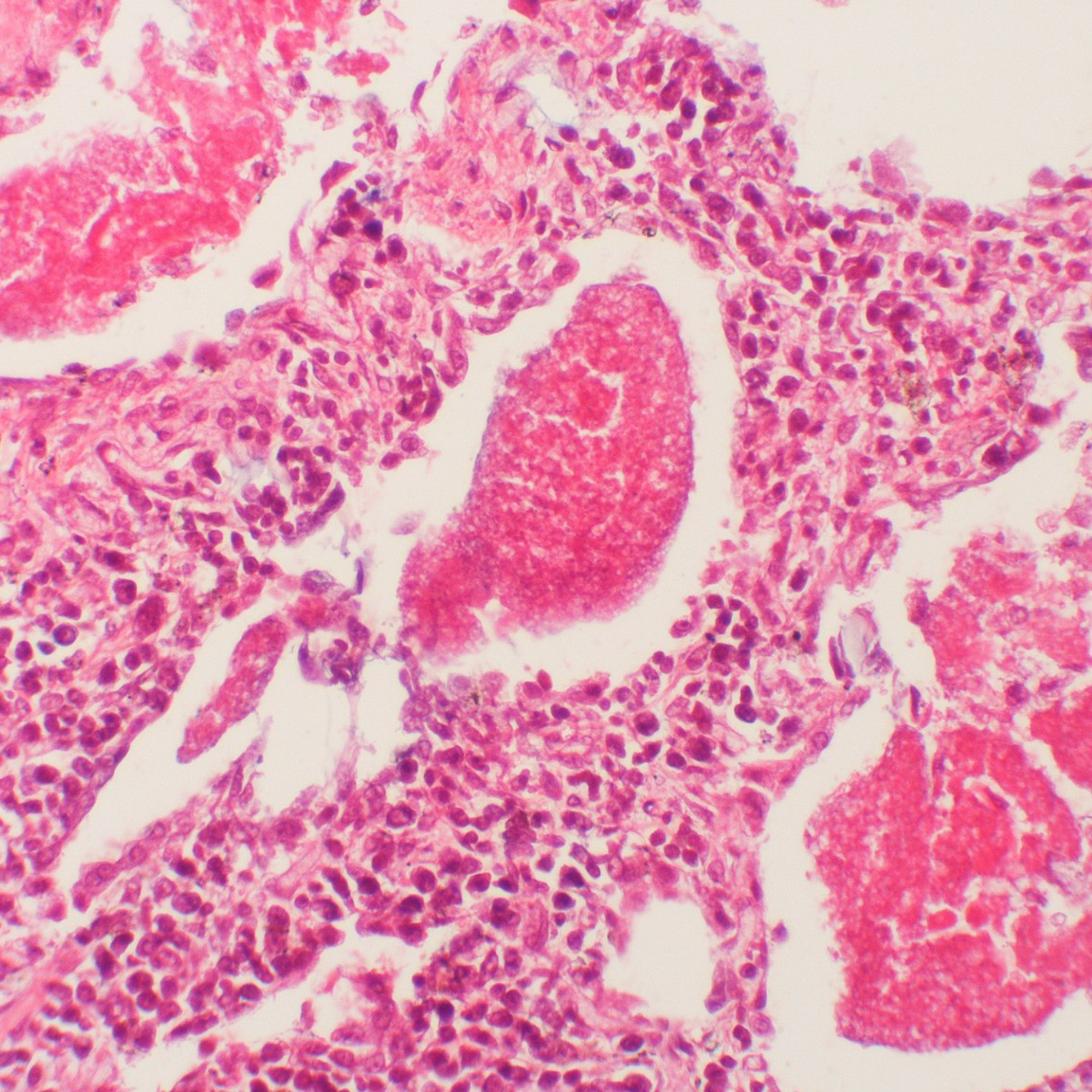

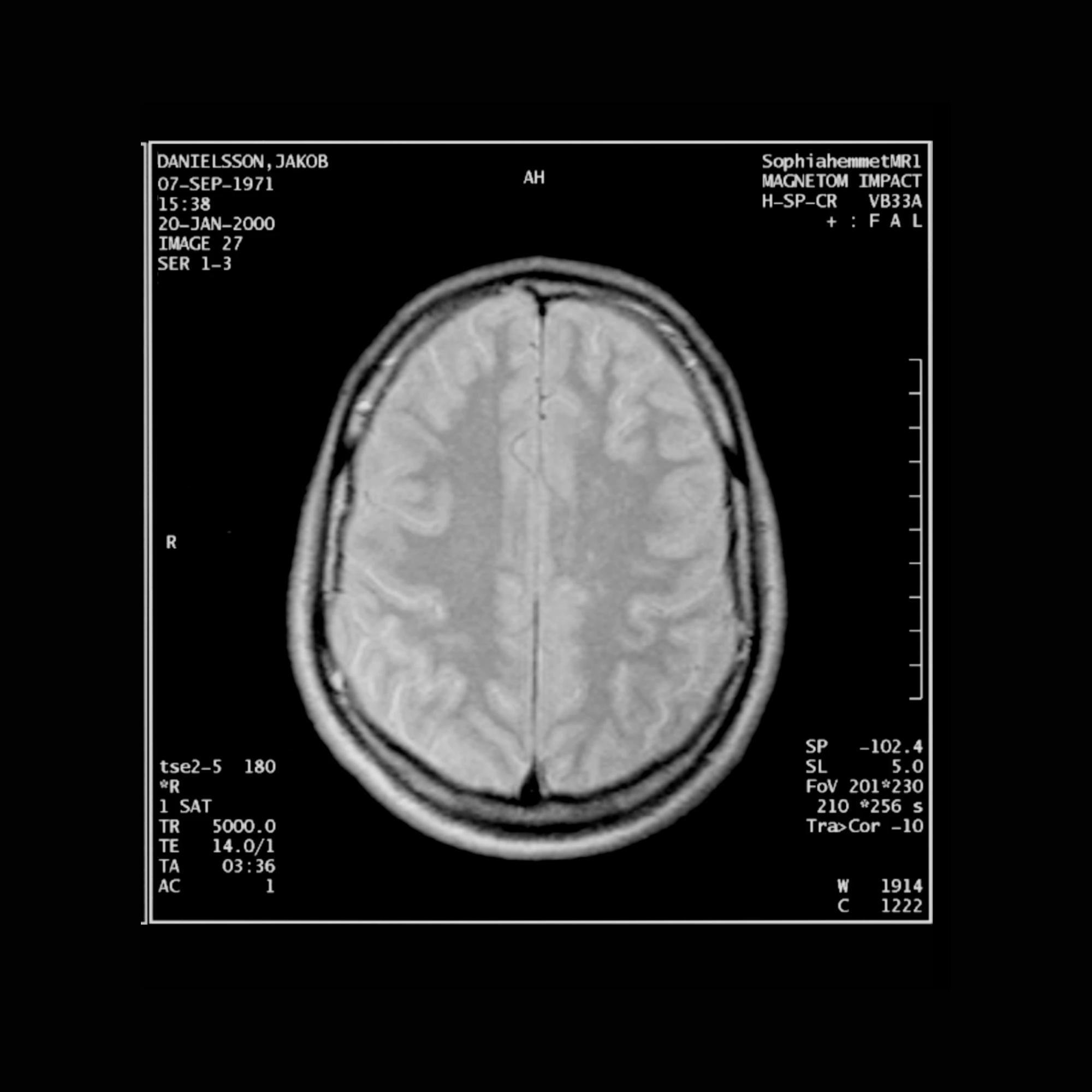

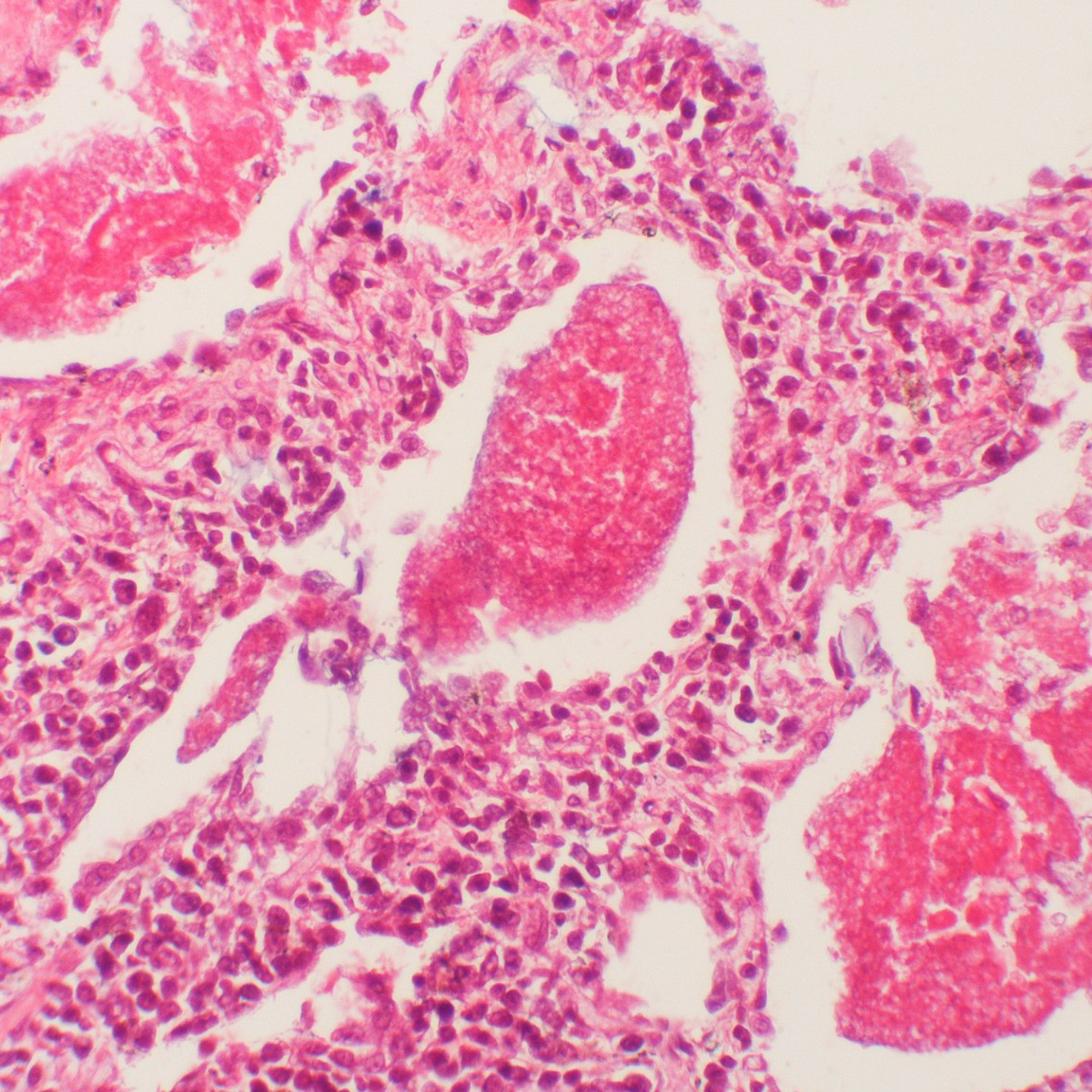

| Oct 25, 2023 Art and autoimmunity. |

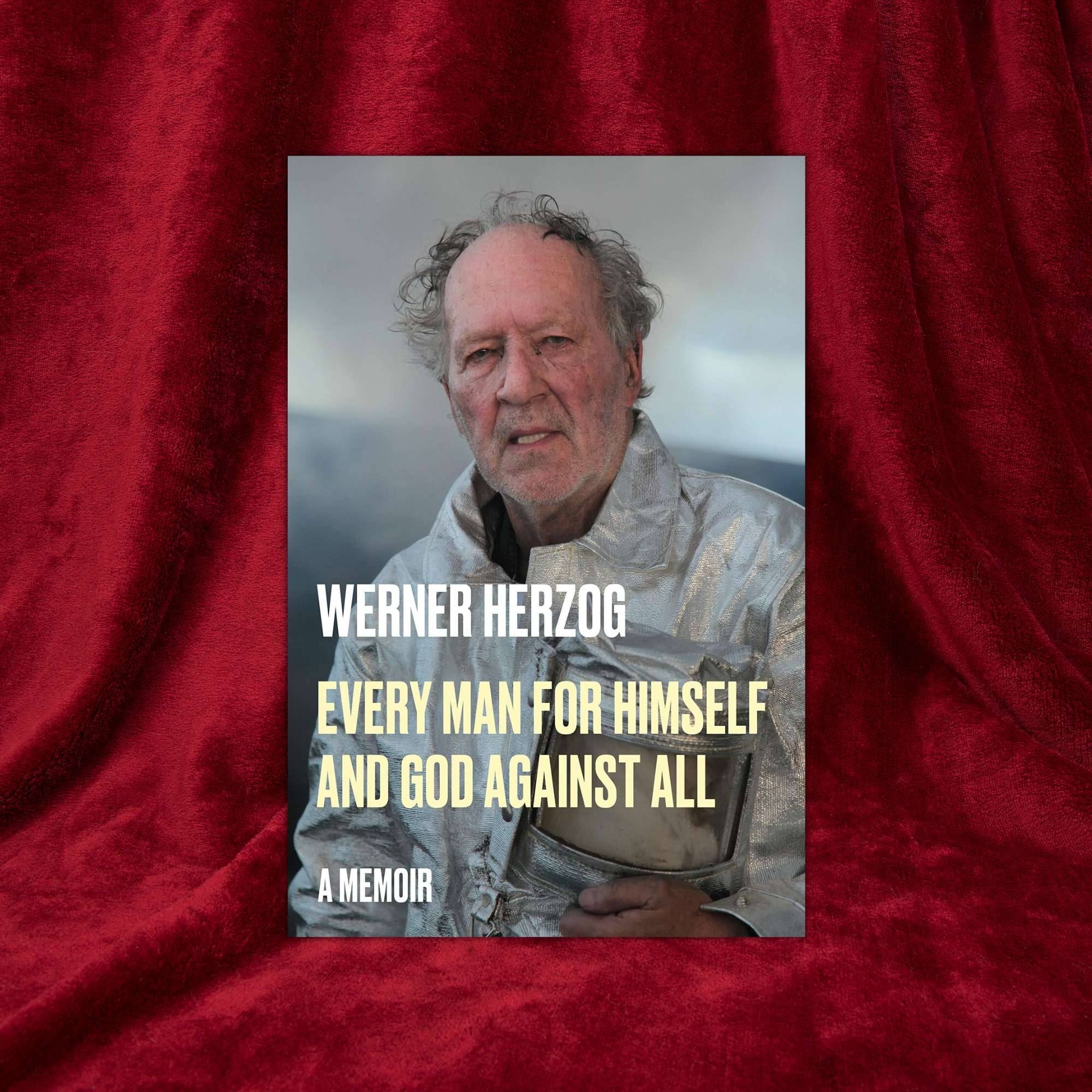

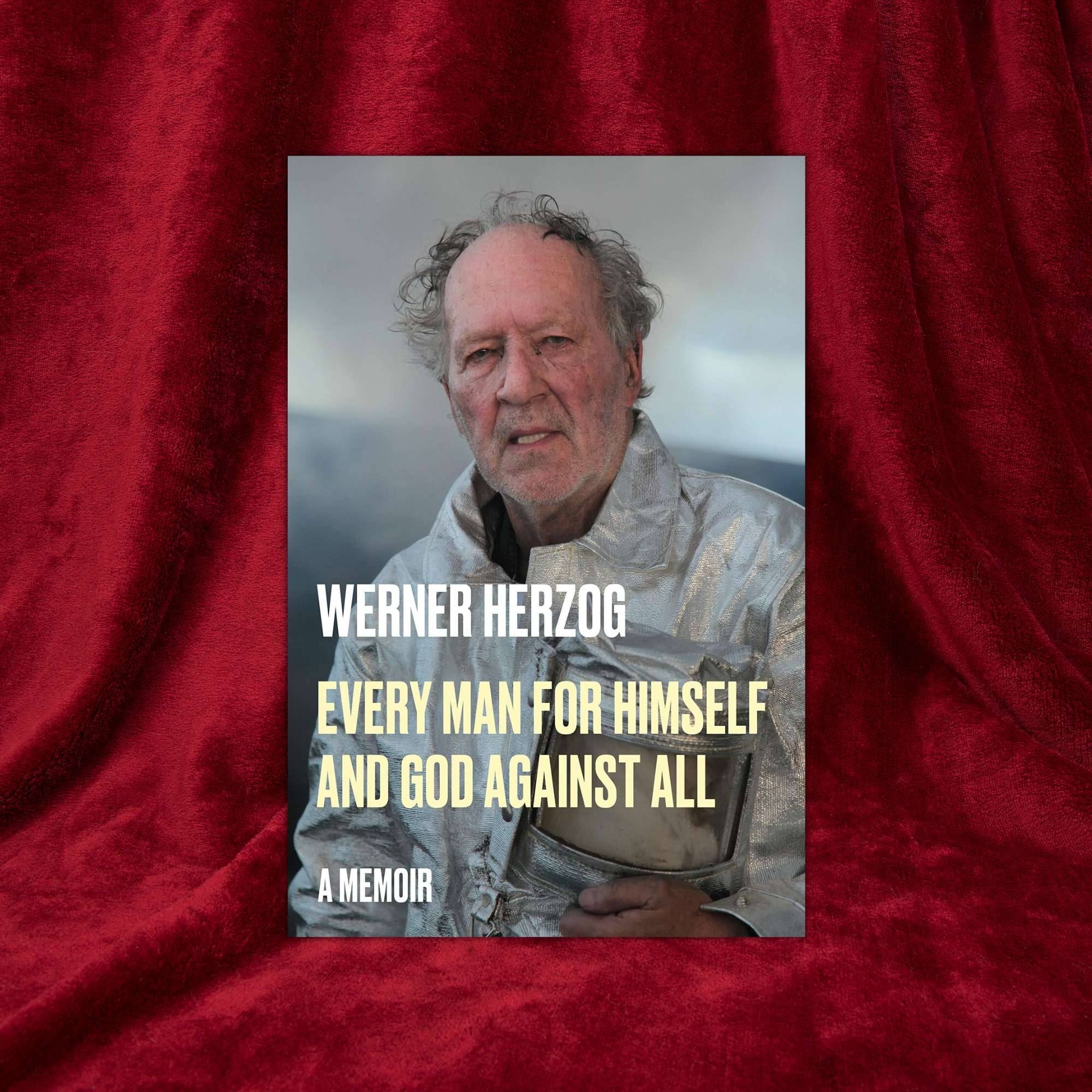

| Oct 24, 2023 The Werner Herzog fandom. |

|

|  | Oct 9, 2023 |

|

|  | Oct 19, 2022 |

|

|  | Sep 22, 2023 |

|

|  | Aug 30, 2023 |

|

|  | Oct 19, 2023 |

|